In 1907, Charles M. Russell painted the watercolor Sun Worship in Montana (fig. 3.1) to be reproduced on the cover of Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly popular magazine, where it was titled “A Blackfeet Indian Mother Holding Up Her Babe to Be Blessed by the Rising Sun.” No other description appears in the magazine, but Russell’s detailed style in the painting heightens visual attention on Native American belongings placed throughout the work—a tipi with a medicine bundle over the door; the figure’s dress, moccasins, knife sheath, and belt—even as he loosely painted the surrounding landscape and the glowing, colorful light emanating from inside the tipi.

For many viewers, such details offer evidence of Russell’s unique access to the culture of the Blackfoot Confederacy (Niitsitapi, meaning “the real people”), enabled by his living near the Blackfeet (Southern Piikani) Reservation in northern Montana.1 Russell displayed the materials he collected on the walls of his studio, as seen in a photograph of the artist at work beneath a warrior shirt, the Blackfeet dress depicted in Sun Worship in Montana, and other Native American belongings (fig. 3.2). Discussing Russell’s collection, Peter H. Hassrick observed that Russell “draped the walls with Indian and cowboy gear collected on area reservations and during his range years, and these artifacts were used liberally as props in his paintings, drawings, and sculptures.”2 While accurate in a broad sense, this statement does not account for the complexity of the transnational exchange that occurred in the making, acquisition, and translation of the belongings into painted motifs. The terms “artifacts” and “props” are misleading and undercut the epistemologies, or worldviews and knowledge systems, that travel through these material forms.

In analyzing Sun Worship in Montana, this essay focuses on these Indigenous epistemologies, embedded by Native American makers in the belongings that Russell collected and painted.3 Taking up the term “belonging” from Native American and Indigenous studies scholars, as well as curators, introduces a vocabulary that distinguishes these material forms from their reframing in settler spaces. Paintings of them enact appropriation, violence, and desire in affirming White artists’ fantasies of western experience for non-Native viewers and collecting of Native American belongings in asymmetrical power contexts. Discussions of art of the American West by White settler artists and their depictions of Native American belongings often perpetuate this violence by treating these materials as mere “props,” “artifacts,” or even “objects,” which implies inanimacy. Imposing a western settler ontology, this framing denies the animacy, relationality, and meanings that Native American makers, often women, imbued in the materials they produced. Made belongings solidify entwinements between material and spiritual realms; bind communities relationally, both among people and with nonhuman entities; and perpetuate cultural continuity through metaphysical animacy.4 For Russell, these belongings are “relics,” but for Blackfoot people, they are relatives.

Scholars often reinforce hierarchies from the Western academy and the field of art history that elevate painting and sculpture over craft. Analyzing Blackfeet and other Native American material forms in Russell’s collection and paintings as belongings points toward a capacious framing of art that includes expressive culture, a more expansive system of aesthetic practice than Western art history, which traditionally overlooks regalia, adornment, figural art, and dance.5 The concept of expressive culture central to Northern Plains lifeways and the expression of Blackfoot knowledge, or Mokakssini, particularly its emphasis on relationality between human and non-human realms, fundamentally differs from Russell’s use of the belongings in his cultural practice.6

Whether or not Russell was aware of the significance of many of the belongings he collected, his paintings speak to these suppressed histories. Perceiving Native American aesthetic and knowledge systems traveling in these paintings through the depiction of these agentic beings opens new methodological frameworks for thinking about the art of the American West and dialogues between White settler and Native American makers. This reading decenters artist intentionality and instead foregrounds the work of scholars from Native American and Indigenous studies and Native American art history, as well as Indigenous knowledge-sharers, to encourage the rethinking of archives and belongings against the grain of settler-colonial possession and histories of repression. This framing encourages an emic methodology, one based on a culture’s internal systems and meanings rather than imposed external frames of reference. An emic method takes seriously Indigenous meanings embedded in the belongings in Russell’s collections by focusing on them in analysis. This approach encourages scholars of art of the American West to study not only American art or the medium of painting but also Native American art history. It enables layered readings of the transnational dialogues between U.S. and Native American artists that are sublimated into painted forms, as opposed to focusing only on settler perspectives, which parse painting as art and material culture as artifact.

The belongings that western artists like Russell acquired do not acquiesce to their appropriation; relatives and animate relations do not succumb to objectification as relics, artifacts, or props. Rather, belongings offer knowledge and truths beyond Russell’s awareness or grasp; Indigenous meanings cannot be effaced in Russell’s re-presentation of them. Focusing on the material forms and their resonance for their makers invites new interpretations of Russell’s pictures. This essay presents Russell’s Sun Worship in Montana as a contest of epistemologies and an unacknowledged collaboration between multiple makers. It does so by bringing to the foreground the role of Josephine Wright, a friend of the Russells and a model in the artist’s practice; taking a close look at some of the Native American belongings that appear in the watercolor; and considering Russell’s debt to beading as a possible point of entry to abstraction.

Posing

Josephine Wright was a Blackfeet model who posed for Native American female figures in a large number of Russell’s paintings in oil and watercolor, as well as sculptures. Wright is scantly mentioned in the scholarship, but once her visage is recognized, it becomes clear that she circulates through much of Russell’s work, as Wright’s granddaughter, Nancy Josephine Clark, showed in a talk at the C. M. Russell Museum in 2018.7 Wright became involved with Russell’s art practice through her friendship with Nancy Cooper, who married Russell in 1896. Wright and Cooper met as live-in household help, cleaning and raising children at the home of Ben and Lela Roberts in Cascade, Montana. In 1900, Wright began living with the Russells and was listed on the census as a boarder and student.8 When Wright married Northern Pacific Railroad worker Fred Tharp in 1903, the Russells acted as witnesses. Charles Russell decorated the back of the wedding certificate with drawings of the bouquet.9

On the side of her mother, Angeline Gobert, Wright was Blackfeet; some census records identify her as White, but she also appears on the Blackfeet Reservation census in 1936.10 We have few details about Wright and Russell’s conversations about Blackfeet life, but she often appears in photographs in Russell’s studio, situated visibly as an interface between the painter and his ever-growing collection of Native American belongings. In one, they sit on the floor among Hudson’s Bay trading blankets in an alcove in the Russells’ home in Great Falls (fig. 3.3). Wright wears a bead necklace over a hide dress lined with beadwork. The alcove is filled with Native belongings, including two painted hides, a tobacco bag, a shield, a medicine bundle, a buffalo-horn bonnet, a backrest, and more. Wright sits adjacent to a bison skull, an ominous symbol of Native American declension, but she is active, alert, and leans into conversation with Russell holding a calumet, or peace pipe. Later photographs taken outside Russell’s log cabin studio depict Wright with her long brown hair in braids, wearing the Blackfeet dress that often hung in the studio (fig. 3.4).

Wright’s presence circulates throughout Russell’s work, including in Sun Worship in Montana. Russell flexibly adapted her visage, so his paintings are more genre scenes built on Wright as a model rather than portraits of her. For example, Rick Stewart and Jodie Utter have observed how Russell anglicized an initial sketch of Wright in the translation from life sketch to watercolor to magazine illustration.11 Yet we can trace, as James Moore did for Taos Society of Artists painter Ernest Blumenschein’s long-term relationship with one of his models, how Wright, as a Blackfeet woman working in Russell’s studio, operates simultaneously in two worlds amid tremendous change for her nation and the repression of her community’s right to practice religion, culture, and custom.12 As a model, we might assume she is playing herself, but as Judith Butler observes, an unknowable gap exists between interior selves and exterior projections, as in the subjective self and the performative, intersocial self we present, a distinction Wright might have leveraged to navigate assimilation policies and to affirm her Blackfeet identity in performance through Russell’s paintings.13 In Sun Worship in Montana, the figure partakes in Russell’s imagining of ancestral Blackfeet practices then discouraged by the U.S. government. She holds a beaded cradleboard up toward the sun, flanked by a Blackfeet tipi with a medicine bundle over the door and a travois to aid with moving camp. The scene centers women’s roles in Blackfeet society in managing the lodge, childrearing, and the intergenerational transmission of spiritual life, though it does not show any known Blackfeet practice of sunbathing a child in a cradleboard.

For non-Native viewers of Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, a representation of sun worship might register as the Sun Dance, a practice outlawed by Canada and the United States that continued in a modified version syncretically along with Fourth of July events, as also discussed by Annika K. Johnson in this volume.14 Annually, bands within the Blackfoot Confederacy gathered during the Ako-katssin, or “time of all people camping together,” to affirm kinship ties and perform Sun Dance rituals. The giveaways, in which people would offer fine belongings to show generosity and affirm kinship ties, represent how, in historian Blanca Tovías’s words, “every Blackfoot activity can be linked to a wider realm wherein animate and inanimate beings impart knowledge and share their power with humans.”15 This practice continued in more localized and syncretic contexts after settler colonialism. Even posing for a painting relating to Blackfeet cultural practices then forbidden might have affirmed Wright’s connection with Blackfeet culture, and the red, white, and blue touches on the watercolor for a late June issue of the magazine speak to both celebrations.

Census reports and newspaper articles show that Wright and her husband had moved to Missoula by 1910.16 By about 1913, the Tharps had moved to the Flathead Reservation, where both of their children were born.17 The couples’ friendship continued; later photographs show the Tharps with the Russells, and Wright’s visage appears in many of Russell’s later artworks. The couple named their son Russell; a photograph from about 1917 depicts Wright and her son, Russell Tharp, on the porch of Charles Russell’s Great Falls studio (fig. 3.5). The baby is nestled inside a Flathead beaded cradleboard. Wright sits proudly beside her offspring, the cradleboard symbolizing their intergenerational connection, filtered through a design imbued with love. As Oglala Lakota curator Emil Her Many Horses notes, “Considered gifts from the Creator . . . the construction, beading technique, designs, and colors on each of these cradleboards are meant to physically and spiritually protect a child.”18 Every bit of its back surface is covered with brightly colored beads in greens, pinks, reds, and blues, along with red wool embossed with sinuous flowering stems. Its symmetrical design prescribes a sense of order and balance in the universe. Its floral motifs signify growth, flourishing, and the transfer of relational knowledge embedded in the Native American belongings that were often depicted in Russell’s pictures.

Circulating

Russell’s imagined West was fundamentally shaped not only by Wright’s labor but also by the artistry and labor embedded in belongings, such as the Blackfeet dress she wears in the aforementioned photograph (see fig. 3.4) and that is painted into Sun Worship in Montana (fig. 3.6). The ability to make through adapting animal materials and trade goods, as well as social protocols, was customarily given to Blackfoot women as a spiritual gift from Elk Woman to strengthen kinship ties within all human relational realms.19 Much more than a costume worn in a studio, the dress is a belonging that speaks to Blackfoot Mokakssini, affirming relationality between human, natural, and spiritual worlds. As D. Richard West points out, “Dresses are much more than simple articles of clothing for Native women—they are complex expressions of culture and identity.”20 Kiowa curator and beader Teri Greeves notes broadly of Native American beadworkers, “Each woman was working on multiple levels, not just in terms of knowing how to work with the medium technically, but also how to work symbolically” through the language of beading.21 These ontologies are embedded in Blackfeet dresses, which are typically a two-hide garment made from tanned bighorn sheep hide adorned along the yoke with beaded line stitching, also referred to as lane stitching, in deep blue and emerald-green pony beads and with a seed-bead trim along the dress’s base (fig. 3.7). The dress worn by Wright would have been tanned, sewn, and beaded by a Blackfeet woman, and it follows community convention based on “origin stories [that] explain the ideologies encoded in dress and define the prerequisites for wearing certain markers of distinction.”22 The design of the yoke dips at center to make space for the deer tail, which articulates the human-animal relationship.23 Ornamental jingles, mainly thimbles, which glint in the light of the painting, would have enhanced the dynamism of the dress and produced sound to let others anticipate the woman entering the space.24 The beading includes deliberately interposed beads of alternate colors that interrupt color continuity. As tribal member Nítsitaipoyaaki (Only Girl; Cheryle “Cookie” Cobell Zwang, Blackfeet Nation, Aamskapi Piikani) shared with me (with generous permission to share further), as a child, she learned from elders that the placement of an alternate color bead within a sea of a single color introduced contingencies found in the imperfections of the natural world; this detail indicates an example of how epistemologies become entwined with material form.25 On this dress, an occasional clear bead on an otherwise colored string articulates this maker’s deliberate nod to cultural practices and articulation of the lessons of nature (fig. 3.8).

Many examples of Blackfoot dresses include triangular and oblong designs on their lower part, as seen in a garment made in about 1860 by Siksika Blackfoot Mrs. Running Rabbit (fig. 3.9).26 Referring to the head and kidneys of the animal whose organs softened the hide, these motifs affirm relationality between human and animal realms. The dress that Russell collected does not include these details, which may suggest that he acquired a dress intended for sale or trade rather than for community use. Given that Blackfeet women’s beading collectives—which were formalized in the 1930s and still operate today—long controlled the sale of belongings in trading posts, such as the one in Glacier National Park, it is possible that Russell’s access to dresses of this type was controlled or limited.27 Furthermore, in Sun Worship in Montana, he added forms to this part of the dress that are not present on the dress itself. Rather than the animal head and organ shapes in the dress by Running Rabbit, he applied concentric circles in red, white, and blue, a form not typically found on Blackfoot dresses but not uncommon in quillwork or beadwork disk forms at the center of Blackfoot men’s warrior shirts.28 Russell may have adapted or invented motifs to stand in for the forms he knew would conventionally be present.

Irrespective of whether Russell’s dress is a guarded or adapted version of a Blackfeet dress, along with his alterations to its design in his translation of it, its ability to express embedded Blackfoot Mokakssini is not diluted. Its re-presentation in his paintings does not necessarily occlude or suppress its originary contexts. When Wright wears the dress and it is rendered, why would we imagine such layered meanings would disappear? Would the belongings not retain their epistemological links to Blackfeet culture? Though Russell’s collecting and painting of Blackfoot belongings takes them out of circulation in explicitly Native American contexts, rooted meanings and relational makings inhere in them and coexist with the western fantasy scene he frames around them. Observation of this continued articulation does not redress the histories of genocide and violent dispossession incited by settler colonialism; the dispossession of land and divestment of Native American material forms by the settler state are simultaneous and entwined acts. In their re-presentation by settler artists, scenes like Sun Worship in Montana enact what Chickasaw literary scholar Jodi A. Byrd has called “the transit of empire.”29 But as belongings also travel in these pictures, initiated community members would recognize cultural knowledge there in ways that exceed Russell’s role or interpretation.

Sun Worship in Montana pairs the Blackfeet dress with a key belonging in Native lifeways: the cradleboard. The wood frame of this cradleboard is modeled in the Plateau style, which includes a wooden backboard with a rounded top decorated with geometric patterning and with a malleable buckskin cradle attached, as exemplified by a Ute cradleboard (fig. 3.10). As noted of the Flathead cradleboard the Tharps acquired for their children (see fig. 3.5), the function of such special belongings is consistent across Native American communities. Love, wishes, energies, and prayers are embedded in beaded cradleboards, which operate, in Sicangu Lakota artist Mitchell Zephier’s words, as “an extension of the mother’s womb . . . [and] an extension of the extended family.”30 Family and close community produce the boards and beading, “imbuing [them] with meaning and protective ornaments. They work together, with the baby in mind and in heart, to create the exquisite and durable first earthly bed for their beloved child, their ah-day.”31 For community members who understand these belongings, such representations of multigenerational and community relations retain their signification and significance even as painted and circulated in the mass media.

The designs on the beaded belongings in Russell’s studio bear motifs with meanings that would likely have been unavailable to him, known only to the beader and initiated members of her community. For Russell, for his non-Native contemporaries, and for uninitiated observers today, opacity surrounds the meanings and messages in Native beadwork abstractions, productively protecting Indigenous knowledge.32 As argued by Nítsitaipoyaaki, Ponokaakii (Elk Woman; Marjie Crop Eared Wolf, Blood Tribe [Káínaa]), and art historian Heather Caverhill, regarding Blackfoot responses to German American painter Winold Reiss’s portraits of community members made in Glacier National Park in the 1930s, descendants recognize their ancestors not only in the people depicted, but also in the belongings they wear and hold within the portraits.33 Likewise, as articulated by Apsáalooke (Crow) artist Wendy Red Star through her re-presentations of late nineteenth-century portraits of her ancestors negotiating to retain sovereignty in Washington, D.C., regalia and belongings signify deeply within their communities across generations.34

Regardless of what Russell did or did not understand about these meanings, they are embedded; as Blackfeet historian Rosalyn LaPier has argued about the Blackfeet stories shared with anthropologists contemporaneous with Russell, their misrepresentation and distortion of what stories meant about Blackfeet epistemology do not erase the beliefs implanted there.35 Rooted meanings do not need to be legible to all to be legible to some, a concept that carries over when reading Russell’s scenes. As curator Jill Ahlberg Yohe reminds us, even in the context in which artists’ names are disassociated from their production, “the object’s agency is intermingled with the maker’s intentions; the maker remains present.”36 Discussing Native American meanings and messages within the belongings in Russell’s painting and restoring them to the conversation encourages us to understand these now anonymized women makers as subtle and unacknowledged co-producers of meaning.

Abstraction

Native American women makers of abstract imagery may have subtly influenced Russell’s practice. Spencer Wigmore has observed scholars’ tendency to run headlong into finding the stories in Russell’s pictures, often overlooking the complex materiality and selective moderating between naturalism and abstraction in parts of his pictures.37 What happens when we retune our perception to center his handling of his media? Around the representations of Native American people and belongings, which are often made with precise ethnographic detail, the settings in Russell’s works often dissipate into loose and washy brushstrokes. In Sun Worship in Montana, the foreground modulates between flat-washed areas and gestural strokes that do not always mimetically produce foliage. In the interior of the tipi visible through a palette-shaped door, Russell utilized impasto and abstract passages of color mixing. Such material engagements align with artists’ experiments with modernism in Europe and the United States in the early twentieth century, but Russell often denied an interest in modernism.

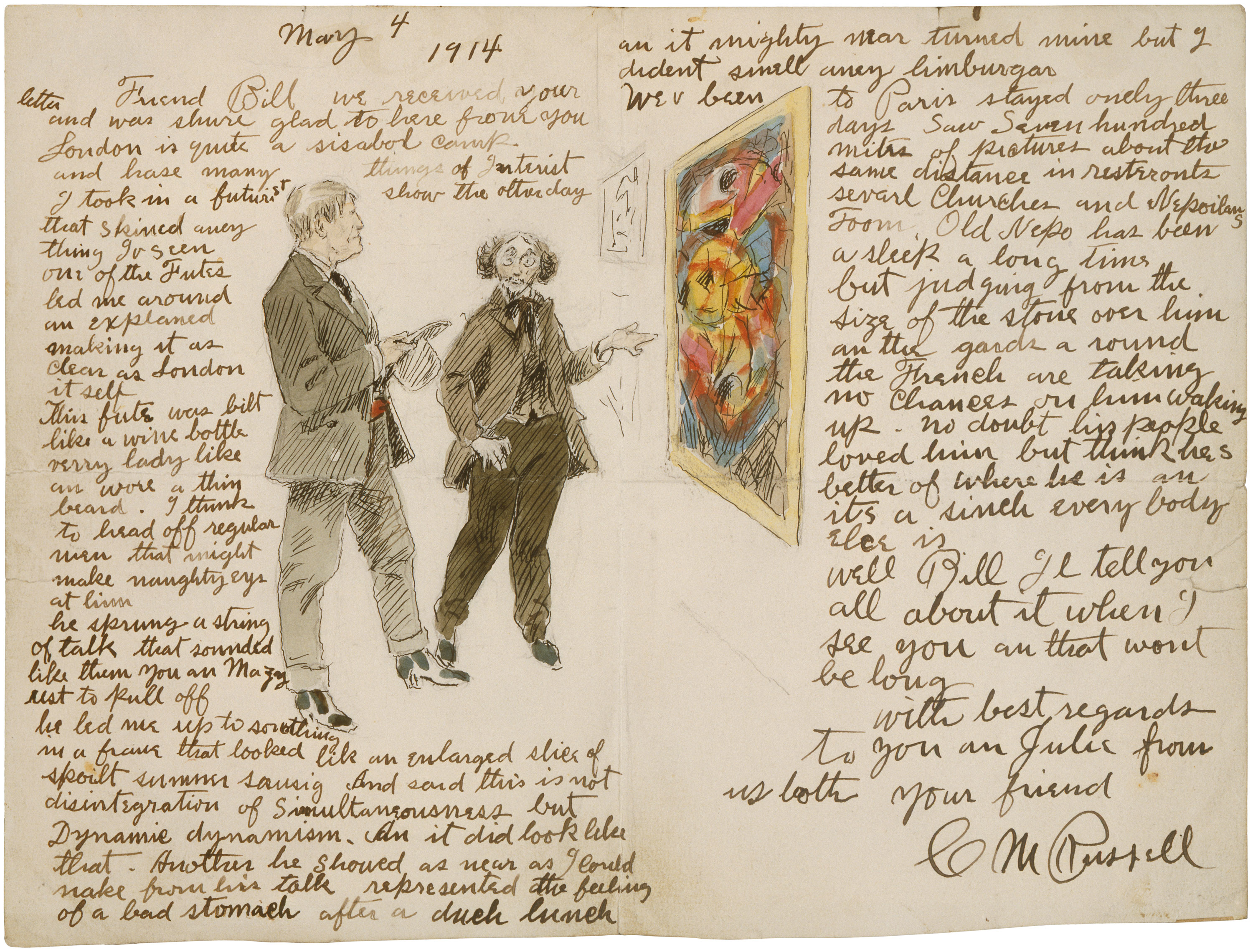

In an infamous letter written after a visit to an exhibition of Italian Futurism taking place alongside Russell’s show at the Doré Galleries in London in 1914, Russell lambasted modernist abstraction (fig. 3.11).38 To a reviewer, Russell joked that if he put his liquored-up friends “in a room with these pictures,” it would “make them swear off [alcohol] for evermore.” He also commented that his “remedy for the women-anarchists would be to shut them in this Futurist gallery” with works that appeared to him as akin to a “child’s kaleidoscope.”39 While mocking modernism, Russell’s facture suggests that he toyed with abstraction via an alternative point of entry: the beaded belongings in his collection. Might we consider the possibility that Russell was, as with many of his contemporaries, turning to artwork from various so-called primitive societies for inspiration, responding to the aesthetic system of beading? Or that he took up the rendering of Native American designs as permission to play with an abstraction that interested him, though he mocked it? In Russell’s engagement, Indigenous designs became abstractions divorced from the stories and symbols emplaced within belongings by their makers, and his free-form appropriation does not suggest understanding of the epistemologies operating around him. Rather, they became aesthetic experiment.

Jodie Utter, a conservator at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, has observed how Russell tended to employ occasional impasto, or buildup of paint, on his surfaces in both oil and watercolor. She notes that Russell often “shaped paint with bright color to convey decoration.”40 In Sun Worship in Montana, Russell included regular dabs of paint along the sash that drapes from the belt (see fig. 3.6). Was Russell treating painting like beading, in the same way that the graphics in Reiss’s portraits of Blackfeet sitters often drew on Blackfeet patterns?41 Russell deliberately flattens the scene and delights in shapes, parceling color in unmixed layers of media. Beading and painting both parcel color, especially in the artist’s rendering of the strong shadows. Might we see an ambivalent modernism emerging, instead of from scorned Futurist painting, from unspoken dialogues with the intricate patterns of Native American belongings? Where else in the pre-World War I era can art historians trace appropriations of Native American design in paintings by White settler artists? Russell’s re-presentations of beadwork, and its possible influence on his own style, are more about surface texture, rather than a deliberate synergy with Blackfoot beliefs in animacy and relationality articulated by the belongings. Perhaps Russell’s attention to beadwork as color and design results from his lack of access to the deeper meanings embedded in the operations of pattern, geometry, emotion, and visual flux between positive and negative space in designs in the broader Blackfoot functions of beadwork.42

Addressing the aesthetic influence beaded surfaces may have had on Russell’s art practice helps to rebalance histories of abstraction, which typically omit the multigenerational abstractions of women beaders from the study of modernism. As Métis artist Jason Baerg argues, “It is important to reclaim the process of Abstraction from Modernist acculturation and legitimize it as a vital Indigenous space of creative inquiry.”43 To Blackfoot makers and community members, these motifs are not abstract but rather part of an interwoven, “invisible reality,” to draw on LaPier’s term. Baerg critiques art history’s omission of Indigenous abstraction in its historiography, which valorizes flatness and material experimentation largely in the context of Europeans’ “discovery” of abstraction in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: “Indigenous abstraction is still recovering from the colonial absorption of appropriation into Western art history.”44 Art historians Ruth B. Phillips and Janet Catherine Berlo are rightly critical of the complete erasure of Native women’s “achievements in abstraction” in multiple media.45 Because of this unjust approach, Native American women artists’ engagements with and contributions to aesthetic abstraction since time immemorial have been suppressed, along with the meanings traveling through their belongings.

Conclusion

Inupiaq artist Stephen Foster and Snohomish leader Mike Evans note that the objectification of Native American belongings in new contexts centers “surveying” rather than “relationships,” placing them in a “fiction of non-relational reality.”46 This powerful phrase speaks to how Russell repurposed the Native American belongings in his collection as artifacts, yanking them out of their relational context and inserting them into his framing of an “Old West.” They operate as salvage ethnography, predicated on the demise and assimilation of Native American people. Russell positioned himself as a cultural broker for Blackfoot people, and there is appropriation and erasure in that power imbalance, especially in rendering a nostalgic pre-contact history that elides the realities of cultural suppression, political repression, and dispossession.

Present-day viewers risk reasserting that colonial perspective by continuing to understand belongings as “props.” Reading Native American art in settler contexts in this way, in other words, reifies settler intent as the definitive interpretation that outweighs all others. Western painters like Russell occupy a position of representational power that allows them to putatively own the objects and their meanings. As Foster and Evans put it, “The imposition of colonial ontological frames of representation is fundamentally colonizing.”47 This focus forecloses the agency, art practices, and politics of Native American artists and objects by implying that they yield and bend to settler intentions, flattened metaphorically as they are translated by settler artists like Russell into two dimensions. Russell’s paintings depend on these belongings to substantiate their own claims, but that relationship is not reciprocal; rather, the Native American belongings supersede the painting. Native American art is trafficked through Sun Worship in Montana and its mass circulation in a popular magazine, but these belongings are also traveling through it. The painting becomes only a stopover on their larger journey, which anthropologist Rosemary A. Joyce frames as “object itineraries.” Tracing belongings’ significations in a variety of contexts can affirm spatial and temporal mobilities and focus attention on “the relationality of things.”48 Recognizing the uneasy coexistence of contingent perspectives and re-centering Native American ontologies, epistemologies, and knowledge systems in Russell’s studio and paintings recuperates sublimated but ongoing challenges to settler colonialism through visual sovereignty.

Since the operations of Native American societies’ worldviews and cultural belongings are incommensurable with Western epistemologies and the visual practices of a settler-colonial society, this essay proposes the need to engage new tools to build mutually coextensive expertise crossing the art of the American West and Native American art histories and to accommodate multiple modes of looking and interpretation simultaneously. This essay offers an intellectual intervention to point to Russell’s dependence on Indigenous knowledge as conveyed by his model and by the belongings in his collection, as well as on Blackfoot art and design. Re-storying Russell’s Sun Worship in Montana to focus on its intersections with Blackfeet and other Native American beliefs, practices, and belongings decenters Russell’s ambitions for his pictures to consider the ways in which other meanings are articulated, even unexpectedly, by the Native American belongings in the scene.

Never painted by Russell, the Flathead cradleboard acquired and used for the Tharps’ children (see fig. 3.5) is now in Russell’s studio collection (fig. 3.12).49 As with the clear bead in the Blackfeet dress worn by Wright (see figs. 3.7, 3.8), this cradleboard bears a single alternate color bead of deep blue within a green field placed directly at the child’s eyeline. Its importance for family and community histories is articulated by the inclusion of the photograph of Wright and baby Russell (see fig. 3.5) in a family album now in the possession of the Tharps’ granddaughter, Nancy Josephine Clark, who is named after both Nancy Russell and Josephine Wright and who presently lives in Seattle. Based on this black-and-white photograph, Clark, who is an artist, recently painted the board’s fecund motifs, surrounding them with protruding arrows that represent, in her words, a “moving forward, strength, protection, and positive life transitions,” moving from an origin point in multiple directions as a metaphor of human life (fig. 3.13).50 In her artistic dialogue with her grandmother and with the Russells, Clark highlights both ancestry and futurity. Her artwork articulates how Native American belongings operate as a connective tissue between generations, a sinew between past, present, and future, with their animacy and relationality still traveling if scholars and viewers look for them.

Endnotes

Thanks to Spencer Wigmore and Will Gillham for editorial feedback and discussion. I am grateful for conversations with and/or access to artworks facilitated by Sarah Adcock, Maggie Adler, Sharon Burchett, Heather Caverhill, Nancy and Ron Clark, Olivia Cotterman, Meagan Evans, Alicia Harris, Jennifer R. Henneman, Annika K. Johnson, Ian Sampson, Jodie Utter, Cookie Cobell Zwang, and Kim Wilson, who provided genealogical research on Josephine Wright. I benefited from presenting this research with the Paper Forum at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art on March 27, 2024.

-

The term “Blackfoot” refers to the wider confederacy, while “Blackfeet” refers to the Southern Piikani who were based nearest to Russell’s home, studio, and log cabin in Glacier National Park. ↩︎

-

Peter H. Hassrick, Charles M. Russell (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989), 85. Published lists include The Log Cabin Studio of Charles M. Russell: Montana’s Cowboy Artist (Great Falls, MT: C. M. Russell Museum, 1931; undated reprint), 15–29; and Elizabeth A. Dear, C. M. Russell’s Log Studio (Great Falls, MT: C. M. Russell Museum, 1995), 23–51. ↩︎

-

Sources that gloss this distinction include heather ahtone, “Considering Indigenous Aesthetics: A Non-Western Paradigm,” Newsletter for the American Society for Aesthetics 39, no. 3 (Winter 2019): 3–5; ahtone, “Shifting the Paradigm of Art History: A Multi-sited Indigenous Approach,” in The Routledge Comp edanion to Indigenous Art Histories in the United States and Canada, ed. Heather Igloliorte and Carla Taunton (New York: Routledge, 2022), 42–52; Carolyn Smith, “Northwestern California Baskets and Weaving the Roots of Home,” presentation at Native American Art Studies Association, October 12, 2023; Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves, introduction to Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists ed. Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Terri Greeves (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2019), 22; Maureen Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum: The Story of a Contested Repatriation of Anishinaabe Artefacts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016), 20–21, 49–79, 103–38; and Tim Ingold, “Rethinking the Animate, Re-animating Thought,” Ethnos 71, no. 2 (2006): 9−20. The digitally archived 2025 symposium “Belonging: Native American Art in Settler Contexts” at the Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma also probed this concept; see “Welcome and Session 1: Defining Belongings,” March 7, 2025, accessed April 11, 2025. ↩︎

-

heather ahtone, “The Animacy of Objects,” American Art 38, no. 3 (2024): 3. On the concept of belongings, see Lorén Spears and Amanda Thompson, “‘As We Have Always Done’: Decolonizing the Tomaquag Museum’s Collection Management Policy,” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals 18, no. 1 (2022): 31–41. ↩︎

-

Jenny Tone-Pah-Hote, Crafting an Indigenous Nation: Kiowa Expressive Culture in the Progressive Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 5. ↩︎

-

On Mokakssini, see Rosalyn LaPier, Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers, and the Supernatural World of the Blackfeet (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017); Nimachia Hernandez, “Mokakssini: A Blackfoot Theory of Knowledge” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 1999); Audrey Weasel Traveller, “A Shining Trail to the Sun’s Lodge: Renewal through Blackfoot Ways of Knowing” (master’s thesis, University of Lethbridge, 1997); Betty Bastien, Blackfoot Ways of Knowing: The Worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi (Alberta: University of Calgary Press, 2004); Blackfoot Gallery Committee, Nitsitapiisinni: The Story of the Blackfoot People (Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 2001); and Blanca Tovías, Colonialism on the Prairies: Blackfoot Settlement and Cultural Transformation, 1870–1920 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Nancy Clark, “Josie: The Blackfeet Woman in Charles M. Russell’s Life,” C. M. Russell Museum, June 15, 2018, accessed January 7, 2025. See also Joan Carpenter Troccoli, ed., “Charles M. Russell’s Women: Reality, Convention, and Imagination,” in Charles M. Russell: The Women in His Life and Art (Great Falls, MT: C. M. Russell Museum, 2018), 23; Anne Morand, Your Friend, C. M. Russell: The C. M. Russell Museum Collection of Illustrated Letters (Great Falls, MT: C. M. Russell Museum, 2008), 28–29; and Raphael James Cristy, Charles M. Russell: The Storyteller’s Art (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004), 58. Wright’s life dates are 1883–1938. ↩︎

-

1900 U.S. Census, Great Falls, Cascade Co., Montana. The Great Falls Leader charted Wright’s camping jaunts with the Russells on August 20 and 27, 1901, p. 5. Thanks to Kim Wilson for scouting and sharing sources. Wright is discussed in Joan Stauffer, Behind Every Man: The Story of Nancy Cooper Russell (Tulsa, OK: Daljo, 1990), 54–56, 74; Brian W. Dippie, “‘It Is a Real Business’: The Shaping and Selling of Charles M. Russell’s Art,” in Charles M. Russell: A Catalogue Raisonné, ed. B. Byron Price (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 6–7; Ronald H. Clark, Charles M. Russell Legacies: The Amazing Tales of Charles and Nancy Russell, Josephine Wright, and Nancy Josephine Clark (self-published, 2025), 6–7, 19–21, 24–25, 34-36; and blog posts by Josephine Wright’s great-grandson, Clancy J. Clark, posted May 30, 2018, accessed August 8, 2025. ↩︎

-

Marriage records list the Great Falls wedding on January 27, 1903. Montana, U.S., County Marriages, 1865−1987. See also “Thorp [sic]-Wright,” Great Falls Tribune, January 28, 1903, p. 8. The decorated back of the certificate resides in a private collection, CR.DR276. ↩︎

-

The 1900 U.S. Census and the marriage records list Wright as White. She appears as one-quarter Blackfeet in the Indian Census, Montana, Blackfeet Indian Reservation Agency, December 31, 1936, p. 345. ↩︎

-

Rick Stewart, Charles M. Russell Watercolors, 1887−1926 (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2015), 319. My thanks to Jodie Utter for discussing this evolution with me. ↩︎

-

James Moore, “Ernest Blumenschein’s Long Journey with Star Road,” American Art 9, no. 3 (Autumn 1995): 6–27. On settler impositions on Blackfoot lifeways, see LaPier, Invisible Reality, 10–22; and Gerald A. Oetelaar, “Entanglements of the Blackfoot: Relationships with the Spiritual and Material Worlds,” in Tracing the Relational: The Archaeology of Worlds, Spirits and Temporalities, ed. B. Jacob Skousen and Meghan E. Buchanan (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2015), 131–45. ↩︎

-

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2007), 185, 192. See also Ruth B. Phillips, “Performing the Native Woman: Primitivism and Mimicry in Early Twentieth-Century Visual Culture,” in Antimodernism and Artistic Experience: Policing the Boundaries of Modernity, ed. Lynda Jessup (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 26–49. ↩︎

-

The Russells attended one such event in 1905. See Sumner W. Matteson, “The Fourth of July Ceremony at Fort Belknap,” Pacific Monthly 16, no. 1 (July 1906): 102; Michael P. Malone, Richard B. Roeder, and William L. Lang, Montana: A History of Two Centuries, revised ed. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991), 370; and Joan Carpenter Troccoli, ed., The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell: A Retrospective of Paintings and Sculpture (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 120–21, 124. ↩︎

-

Tovías, Colonialism on the Prairies, 17. See also LaPier, Invisible Reality, 28; and William E. Farr, The Reservation Blackfeet, 1882–1945: A Photographic History of Cultural Survival (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984), 69–96. ↩︎

-

The 1910 U.S. Census in Missoula lists the couple at 518 N. Third Street. See also “Elect Officers,” Missoulan, December 5, 1912, p. 10. The 1936 Blackfeet Agency Census cited in note 10 locates her farther west, in Wallace, Idaho. ↩︎

-

Nancy Josephine Clark, correspondence with the author, April 6, 2025. ↩︎

-

Emil Her Many Horses, ed., “Portraits of Native Women and Their Dresses,” in Identity by Design: Tradition, Change, and Celebration in Native Women’s Dresses (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2007), 79. ↩︎

-

Tovías, Colonialism on the Prairies, 17, 73–¬74; Weasel Traveller, “A Shining Trail,” 94. See also Rebecca Many Grey Horses, “Blackfoot Women: Keepers of the Ways and Pillars of the Nation,” lecture, Galt Museum & Archives, June 22, 2020, accessed June 13, 2025; and Jessa Rae Growing Thunder, “Hi-Line Treasures: Bold Colors and Geometric Designs Exemplify Beadwork from Montana’s Northern Plains,” Native American Art Magazine 38 (April/May 2022): 92–97. ↩︎

-

D. Richard West, “The Story the Dress Might Tell,” in Her Many Horses, Identity by Design, 11. ↩︎

-

Greeves, “Beadwork Conversations: Dyani White Hawk and Graci Horne,” in Yohe and Greeves, Hearts of Our People, 206. ↩︎

-

Tovías, Colonialism on the Prairies, 82. ↩︎

-

Her Many Horses, Identity by Design, 33. ↩︎

-

Her Many Horses, Identity by Design, 62. ↩︎

-

Cookie Cobell Zwang, conversation with the author, Kalispell, Montana, September 20, 2024. ↩︎

-

Her Many Horses, Identity by Design, 33–35. ↩︎

-

Heather Caverhill, “Mutable Modernisms: An Art Colony in Niitsitapi Territory and the Lives of Its Works” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 2024), 81–85. ↩︎

-

Joseph D. Horse Capture and George P. Horse Capture, Beauty, Honor and Tradition: The Legacy of Plains Indian Shirts (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of the American Indian, 2001), 27, 47, 51. ↩︎

-

Jodi A. Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). ↩︎

-

Lois Sherr Dubin, North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment from Prehistory to Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 266. See also MaryAnn Guoladdle Parker, “Vessels That Carried Us: Kiowa Cradleboards,” First Americans Museum, accessed January 13, 2025; Deanna Tidwell Broughton, Hide, Wood, and Willow: Cradles of the Great Plains Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 4–6, 21–23; and Christina E. Burke, “Growing Up on the Plains,” in Tipi: Heritage of the Great Plains, ed. Nancy B. Rosoff and Susan Kennedy Zeller (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 170–73. ↩︎

-

Yohe and Greeves, introduction to Hearts of Our People, 25. ↩︎

-

ahtone, “Considering Indigenous Aesthetics,” 4. On the right to opacity, see Sascha T. Scott, “Ana-ethnographic Representation: Early Modern Pueblo Painters, Scientific Colonialism, and Tactics of Refusal,” Arts 9, no. 1 (2020), accessed January 13, 2025. ↩︎

-

Nítsitaipoyaaki “(Only Girl; Cheryle “Cookie” Cobell Zwang)”, Ponokaakii (Elk Woman; Marjie Crop Eared Wolf), and Heather Caverhill, “‘We Know Who They Are’: Connecting with the Niitsitapi in the Portraits of Winold Reiss,” in [BNSF Railway Catalog], BNSF Railway, ed. Joni Wilson-Bigornia (forthcoming), 28–41. ↩︎

-

Wendy Red Star and Shannon Vittoria, “Apsáalooke Bacheeítuuk in Washington, DC: A Case Study in Re-reading Nineteenth-Century Delegation Photography,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), accessed April 29, 2025. ↩︎

-

LaPier, Invisible Reality, xxxviii. ↩︎

-

Jill Ahlberg Yohe, “Animate Matters: Thoughts on Native American Art Theory, Curation and Practice,” in Yohe and Greeves, Hearts of Our People, 177. ↩︎

-

Spencer Wigmore, “New Perspectives on Charles Russell,” lecture, Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West, University of Oklahoma, March 21, 2023. ↩︎

-

Brian W. Dippie, The 100 Best Illustrated Letters of Charles M. Russell (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2008), 102–3, 111. ↩︎

-

H. T., London Notes, The Cornishman, June 8, 1914, CMR Newspapers, Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. ↩︎

-

Jodie Utter, “The Unconventional Genius of Charles M. Russell: His Watercolor Techniques and Materials,” in Stewart, Charles M. Russell Watercolors, 444. ↩︎

-

Nítsitaipoyaaki, Ponokaakii, and Caverhill, “‘We Know Who They Are’”; Heather Caverhill, “Niitsitapi Belonging(s) in Portraits by Winold Reiss,” third talk in panel, at symposium “Belonging: Native American Art in Settler Contexts,” March 7, 2025, accessed April 29, 2025. ↩︎

-

On this powerful abstraction, see Teri Greeves, “The Women Were Busy Abstracting the World,” in Yohe and Greeves, Hearts of Our People, 99–101. ↩︎

-

Jason Baerg, “Indigenous Abstraction: A Vehicle for Visioning,” in Igloliorte and Taunton, The Routledge Companion, 371. ↩︎

-

Baerg, “Indigenous Abstraction,” 375. ↩︎

-

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, “‘Encircles Everything’: A Transformative History of Native Women’s Arts,” in Yohe and Greeves, Hearts of Our People, 63. ↩︎

-

Stephen Foster and Mike Evans, “Decolonizing Representation: Ontological Transformations through Re-mediation of Indigenous Representation in Popular Culture and Indigenous Interventions,” in Igloliorte and Taunton, The Routledge Companion, 276. ↩︎

-

Foster and Evans, “Decolonizing Representation,” 282. ↩︎

-

Rosemary A. Joyce and Susan D. Gillespie, “Making Things out of Objects That Move,” in Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice, ed. Rosemary A. Joyce and Susan D. Gillespie (Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press, 2015), 5. ↩︎

-

The belonging was acquired by sale or gift between 1917 and 1930; it appears in a 1930 photograph of the interior of the memorial studio, accessed September 15, 2025. ↩︎

-

Clark, Charles M. Russell Legacies, 93. ↩︎