Over the past decade, curators and historians of American art have begun to turn their attention to the rich history of Indigenous artistic production. As the field continues in this vital new direction, it is essential to highlight the contemporaneous works of both Native and non-Native creators. Toward this end, the collections of Indigenous art owned by such well-known painters as Karl Bodmer, George Catlin, Benjamin West, and N. C. Wyeth can provide invaluable starting points for deeper investigation, illumining previously unexamined signs of cross-cultural exchange.1 Such artists’ depictions of Indigenous subjects invite a critique often centered on representational accuracy that, while significant, oversimplifies the inherent tensions of the artist’s role as a participant in cultural exchange.

In this context, Charles M. Russell, renowned for his depictions of the American West, emerges as a distinctive figure. Russell not only painted vivid scenes of Indigenous American life but also amassed a significant collection of Native American cultural belongings—an aspect of his artistic practice that has remained relatively unexamined by scholars. This collection presents a fascinating window into Russell’s studio practice, providing important insights into his encounters with Native peoples, both in his artistic imagination and throughout his life in Montana.2 It also provides us with a unique opportunity to move beyond the identification of stereotypes in Russell’s art and to instead contextualize his career within the era of U.S. allotment and assimilation policies, which had a dramatic impact on Indigenous creative production. This essay aims to provide an introduction to Russell’s collection of Native American cultural belongings, both those he acquired and those he created, while also suggesting avenues for future research into Russell’s art, his studio practice, and his relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Russell’s Studio Collection

Numerous photographs illustrate how Russell filled his studio with Native American cultural belongings, cowboy gear, and objects reminiscent of the Old West (fig. 2.1). His “Indian curios,” as they were called in Russell’s time, range from men’s fringed buckskin shirts and leggings, beaded dresses, gauntlets, and saddles to household items from camp life. After the artist’s death in 1926, much of his studio collection remained intact; today, it forms part of the C. M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Montana. In 1927 Joe De Yong, Russell’s protégé, created a detailed inventory of the artist’s collection that offers crucial insights into the eclectic mix of items that Russell left behind. De Yong’s inventory list includes art supplies such as chisels, modeling clay, varnish, and several paint tubes; personal effects, keepsakes, and photographs; and half-finished paintings, western art prints, Stetson hats, and cigarette rolling papers. In addition, the inventory reveals over 100 items that are either of Native American manufacture or related to Native American culture.3 These encompass beaded regalia and household items from the Northern Plains. Additionally, there are several Diné (Navajo) and Hopi moccasins and ceramics Russell collected during his trip to Arizona in 1916, as well as several facsimile items that were made by Russell.

Most of the Indigenous items in Russell’s collection reflect his surroundings in the Hi-Line region of the Northern Great Plains, with cultural belongings primarily originating from Salish (Flathead), Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Nakoda (Assiniboine), A’aninin (Gros Ventre), nêhiyaw (Cree), and Anishinaabe (Chippewa) communities. De Yong occasionally added annotations to his inventory entries, offering valuable information about the cultural significance, tribal attribution, and history of Russell’s Native collection. This information, along with photographs, letters, and a visual analysis of the remaining Native items in the studio collection, suggests that most of these works were created on reservations between the 1880s and the early 1920s.

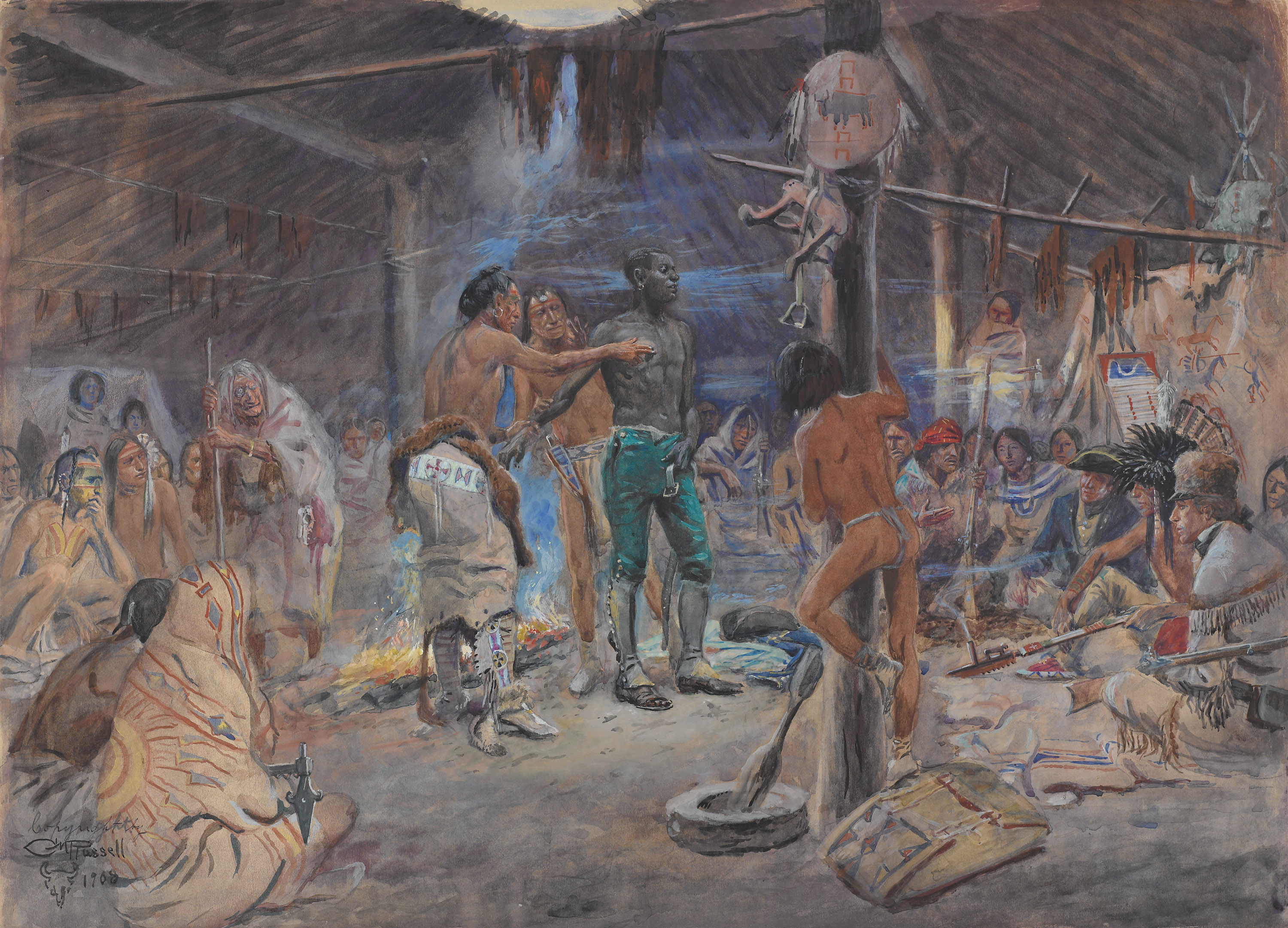

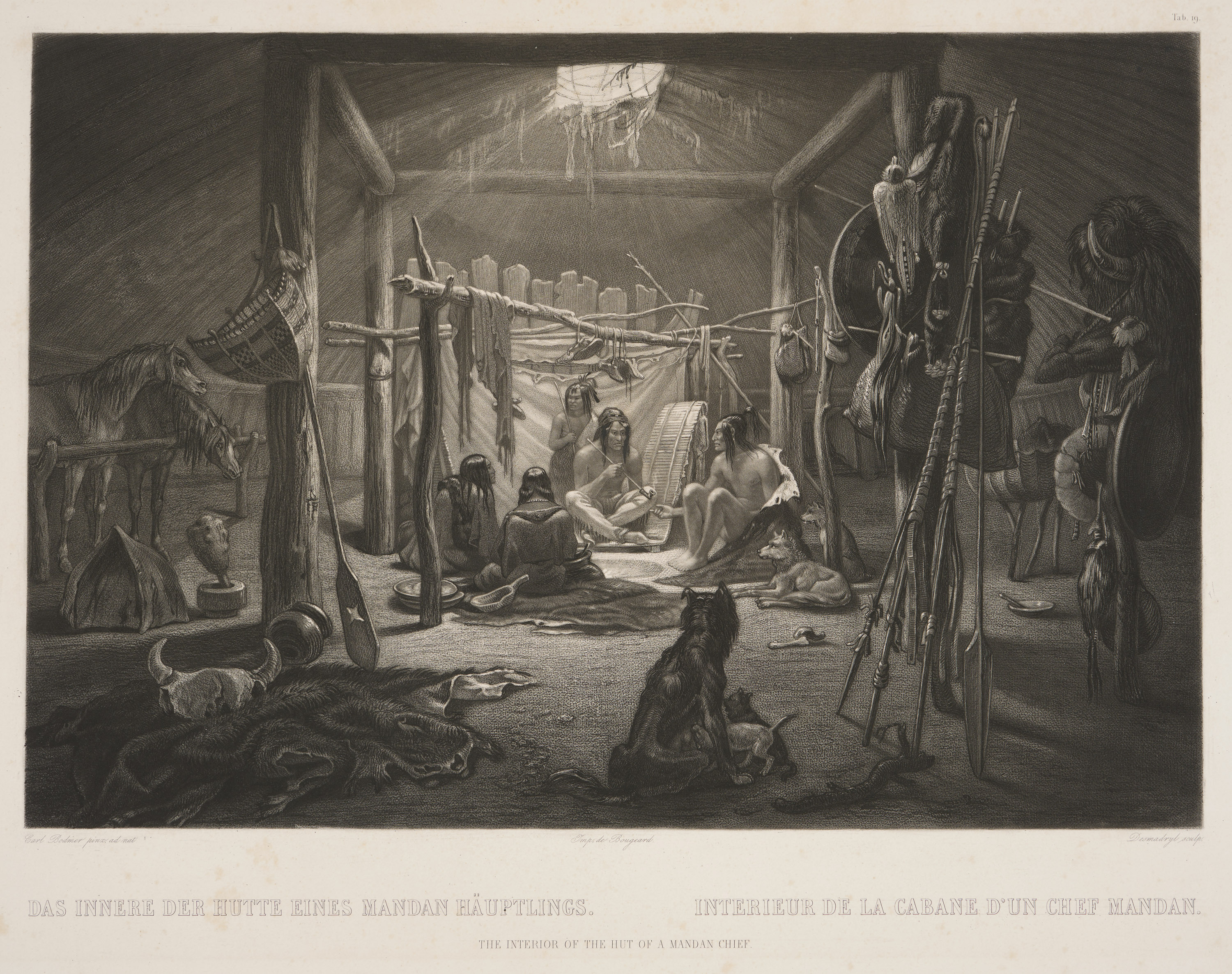

Many of these items made their way into Russell’s paintings and watercolors. These artworks, which include scenes of war parties, buffalo hunts, and daily camp life, reinterpret the items in his collection. Namely, they transpose these materials into the pre-reservation West in ways that complicate our understanding of the artist’s relationship to Native art. Russell often included culturally incongruous items in his work, collapsing decades of changes in Native artistic practice. For example, his painting York reimagines a historical encounter between Hidatsa people and Captain William Clark’s enslaved attendant, York (fig. 2.2). However, the picture includes an abundance of cultural materials from the wrong tribe. Russell based his rendition of this scene on the print version of Karl Bodmer’s The Interior of the Hut of a Mandan Chief, the original of which was created near Fort Clark in the winter of 1833 (fig. 2.3).4 In his adaptation, Russell substituted the Mandan society gear, burden basket, and bullboat paddle featured in Bodmer’s rendering with items manufactured several decades later by Piikani (Blackfeet) people. These include a beaded blanket strip, a knife case, a beaded buckskin dress, a pictorial painted shield and tipi liner, and a willow-branch backrest, items that were modeled after objects in Russell’s studio collection.5 Notably, the bold geometric designs painted in primary colors on the buffalo rawhide container in the foreground directly replicate an example of the sturdy storage container Russell acquired around 1901 (fig. 2.4).6 These items certainly would not have been present in an earth-lodge village in 1804, or even during Bodmer’s visit to the Knife River Indian Villages three decades later.

Rather than explaining these anachronisms away as artistic indulgence or evidence of Russell’s limited understanding of the past, they are an invitation to seek a fuller understanding of the cultural landscape at the turn of the century. The artist’s career unfolded during the era marked by the 1883 Religious Crimes Code, which banned customary dances until 1933 and ceremonies until the act was repealed in 1978. Russell was aware of the profound shifts in Native American material culture that resulted from U.S. policies of displacement and dispossession that took place during his lifetime. Despite his preference for painting what he saw as the authentic Old West, his collection primarily comprises Indigenous art made after the establishment of reservations and decimation of the buffalo. Seen in this light, his collection offers invaluable evidence of the resilience of Native peoples during this transformative era.

Collecting Native Art on the Hi-Line

Russell’s first meaningful encounter with Native American people occurred in the late 1880s, when he journeyed through the Kainai lands in present-day Alberta, Canada. During this trip, Russell spent three summer months in a cabin near Fort Macleod and could have obtained a few items from Kainai communities. However, De Yong’s inventory documents only one object, a buckskin sash, as having been obtained from Fort Macleod in the late 1880s.7 While there could have been more that did not remain in Russell’s studio at the time of his death, it is more likely that at that point in Russell’s career, he lacked the rapport with Native peoples and the financial resources needed to collect in abundance or systematically.8

Russell began collecting Native art predominantly from northern Montana in the early 1890s, coinciding with the consolidation of various rail lines into the intercontinental Great Northern Railway. The main rail line through Montana, called the Hi-Line, borders the Fort Peck, Fort Belknap, Rocky Boy’s, and Blackfeet Reservations, where tribes with distinct languages, lifeways, and artistic styles were forced to permanently settle together in the late nineteenth century. The Hi-Line came to define a regional style of beadwork, which Dr. Jessa Rae Growing Thunder characterizes as featuring “clear moments of distinct tribal styles, but there are also moments when those lines become blurred, and we see the intertribal inspiration contribute to the overarching aesthetics of the region.”9 The prominent use of Sioux-blue and Cheyenne-pink glass seed beads, the flat-stitch beading technique, and the experimentation with bold geometric and floral designs are all Hi-Line characteristics prominent in Russell’s collection of Native beadwork. In turn, they offer evidence of the ways that artists created new visual forms amid a rapidly changing environment shaped by the near extinction of buffalo, the economic dominance of cattle ranching, and the emergence of the cultural tourism industry in Montana. As artists shifted to using materials like cowhide and wool, gained access to a broader range of bead colors at a lower cost, and spent extended periods on reservations, their beadwork became more elaborate. These conditions set the stage for the creation of non-ceremonial garments and objects intended for cultural outsiders that diverged from earlier, community-specific needs and traditions.

The Fourth of July gathering held on the Fort Belknap Reservation in 1905 was the kind of federally sanctioned social event at which Russell could acquire beadwork from this region. Native families adopted the U.S. holiday to honor their tribal veterans and socialize through mock battles, horse racing, hand games, and traditional meals. Local newspapers promoted these multiday gatherings, which were attended by hundreds of families from reservations across northern Montana as well as non-Native visitors who traveled to reservations by rail.10 At the time of the 1905 gathering, Fort Belknap was home to two distinct, previously opposing nations of A’aninin and Nakoda people, both of whom were facing substantial pressure to cede additional lands to White settlers, this time opening some 40,000 acres of tribal lands along the Milk River. The Great Falls Tribune expressed the patronizing attitude that the Indians had “entirely too much land for them to handle . . . they must secure more money or work like white men.”11 Congress would approve the cession later that year, diminishing the tribes’ land holdings and challenging their water rights.12 Despite these assaults on Native sovereignty and traditions at the turn of the century, families continued to practice the Sun Dance, Grass Dance, and other summertime ceremonies in secret as well as under the guise of American patriotism.

According to De Yong’s inventory, Russell received a shirt and a pair of leggings from an A’aninin man named Big Bear on the Fort Belknap Reservation during what the artist referred to as a Medicine Dance. Both items show signs of wear that indicate they were made for tribal use rather than for sale to non-Natives. The shirt, made of cropped deer hide, features wool-wrapped ermine fringes adorning the shoulders and arms—decoration characteristic of the Northern Plains. Two wide strips of flat-stitch beadwork extend from the front of the shirt, over each shoulder, to the middle of the shirt’s back (fig. 2.5). De Yong identified the shirt as being from the Fort Belknap Reservation, an assessment supported by the geometric checkered and elongated diamond patterns; the color combination of forest green, pumpkin orange, greasy yellow, and navy blue; and the incorporation of white hearts and steel-cut beads, all set against a dark periwinkle beaded background.13 Unlike the flat-stitch beaded shirt strips, the geometric lodge designs on the legging strips were beaded using a technique called the “lane stitch,” comprised of parallel rows of six to eight beads per stitch (fig. 2.6). The coexistence of Northern and Central Plains beading techniques reflects the diversity of traditions that coexisted on the reservation and may even indicate that the shirt and leggings were created by different artists from different tribes.

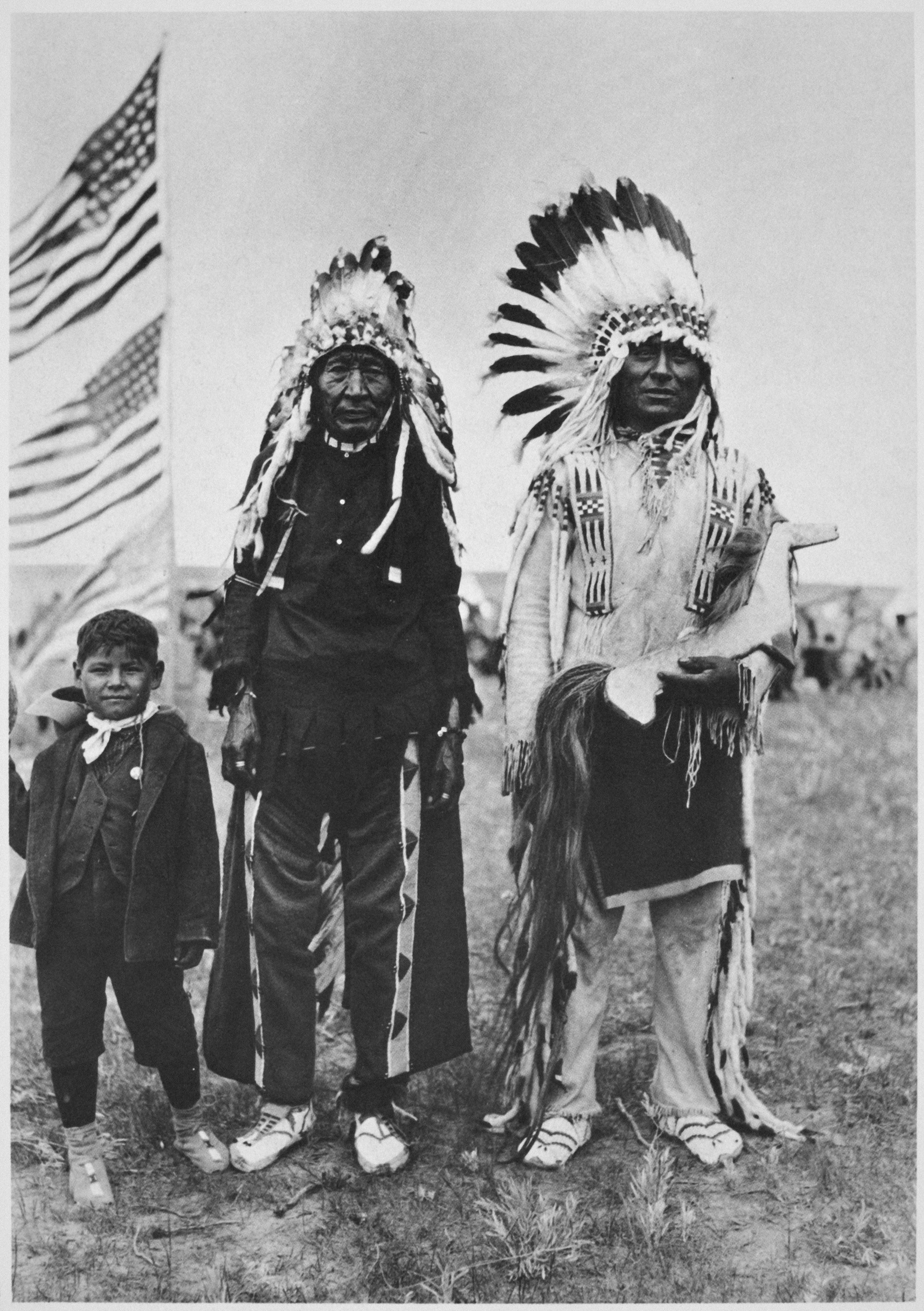

This shirt and leggings appear in several photographs taken by Sumner W. Matteson, an itinerant photographer from Iowa who traveled to Fort Belknap in the company of Charles Russell and his wife, Nancy. During the visit, Matteson documented the dances, battle reenactments, feasts, and giveaways that occurred over several days, and he published his findings in the Pacific Monthly in 1906.14 Several of his photographs show a man wearing the shirt and leggings that Russell had acquired (fig. 2.7). While research has not conclusively identified the sitter, it is believed to be Big Bear himself, who had corresponded with Russell and received numerous photographs, drawings, and carvings from the artist.15 Perhaps the artist received the garments as a token of friendship, or during a giveaway, a traditional practice of gifting blankets, regalia, and even horses to the community in honor of an individual. George P. Horse Capture, reflecting on Russell’s time with the A’aninin people, recounted that “the Indian people gave beautiful gifts to Russell as well; exchanging gifts is a custom among us.”16 Even if we do not know the exact circumstances of the exchange, Russell was a familiar presence on the reservation and had developed friendships with individuals like Big Bear and the well-known A’aninin elder Bill Jones.17

Russell prominently displayed the shirt and leggings from Big Bear in his Great Falls studio, and these garments were also worn and used, including by people from different tribes. In a 1916 photograph, an Anishinaabe elder and spiritual leader named Chief Big Rock donned the Fort Belknap regalia and posed with Russell and the writer Frank Bird Linderman in front of a tipi (fig. 2.8). The photograph was taken to commemorate Big Rock’s trip to Great Falls to share traditional stories with his longtime acquaintance Linderman for the book Indian Old-Man Stories: More Sparks from War Eagle’s Lodge-Fire (1920). Russell, who was to illustrate the publication, made an elaborate production of the four-day visit, erecting a tipi in his neighbor’s backyard and furnishing it with domestic items from his collection.18 The meeting garnered the attention of the press, and Russell possibly lent the outfit for Big Rock to model in an effort to maintain a more “authentic” appearance. The three well-known men were also advocates for the landless Anishinaabe, nêhiyaw, and Métis refugees who had suffered years of forced relocation and broken promises. Linderman had led the effort to raise awareness of the mistreatment of the landless families among White Montanans, garnering the support of colleagues like Russell.19 In 1916, Congress passed legislation establishing Rocky Boy’s Reservation in northern Montana, west of Fort Belknap.

This moment of public advocacy emerged from personal relationships that involved the exchange of stories, support, and gifts. In Northern Plains communities, reciprocity is a core value, grounded in kinship, mutual obligation, and the ongoing care of relationships. These principles shaped the ties between Russell and his Native acquaintances and find clear resonance in Russell’s collections. Two brothers named John Young Boy and Buffalo Coat, both members of Little Bear’s landless band of nêhiyaw people, exemplified this tradition. They often visited Great Falls and exchanged gifts with Russell, marking a friendship that began in the 1880s and continued after the establishment of Rocky Boy’s Reservation.20 In 1900, Buffalo Coat presented Russell with a capote, an iconic style of Northern Plains hooded coat crafted from a Hudson’s Bay blanket, which Russell often wore and incorporated into many of his paintings (fig. 2.9).21 In commemoration of this gift and their friendship, Russell depicted Buffalo Coat with a capote draped over his left shoulder in a portrait dating to 1908 (fig. 2.10). Young Boy also modeled for the artist, and the two exchanged many gifts. In a 1902 letter to Young Boy, Russell expressed gratitude for a painted shield that, though currently unlocated, is illustrated in Russell’s letter as an object adorned with eagle-feather ornaments and pictorial scenes.22 In the later years of their friendship, Young Boy presented Russell with an exquisite set of contemporary cuffs and matching armbands, adorned with intricate contour beaded floral designs set against a solid white, flat-stitch beaded background bordered by a distinctive Hi-Line parapet design (fig. 2.11).23 Eye-catching cuffs in this style became popular rodeo attire in the early twentieth century, ultimately evolving into a hallmark of powwow regalia. Beaded gauntlets in Russell’s collection showcase a related style of trade accessory that was fashionable among Native and non-Native individuals during his era. Intricate floral motifs appliquéd on two examples of beaded gauntlets in Russell’s collection were likely made by the same woman, whose name, unfortunately, remains unrecorded.24

Russell’s collection of Native art was shaped by personal relationships and historical conditions specific to the Hi-Line region. The forced consolidation of Native communities on reservations, emergence of a distinctive beadwork style, and reservation gatherings created opportunities for exchange during a period of intense political pressure on Native sovereignty. Gift giving, correspondence, and collaboration with individuals like Big Bear, Young Boy, and Buffalo Coat contributed to a collection that reflects enduring practices of reciprocity.

Replicating Native Art in the Studio

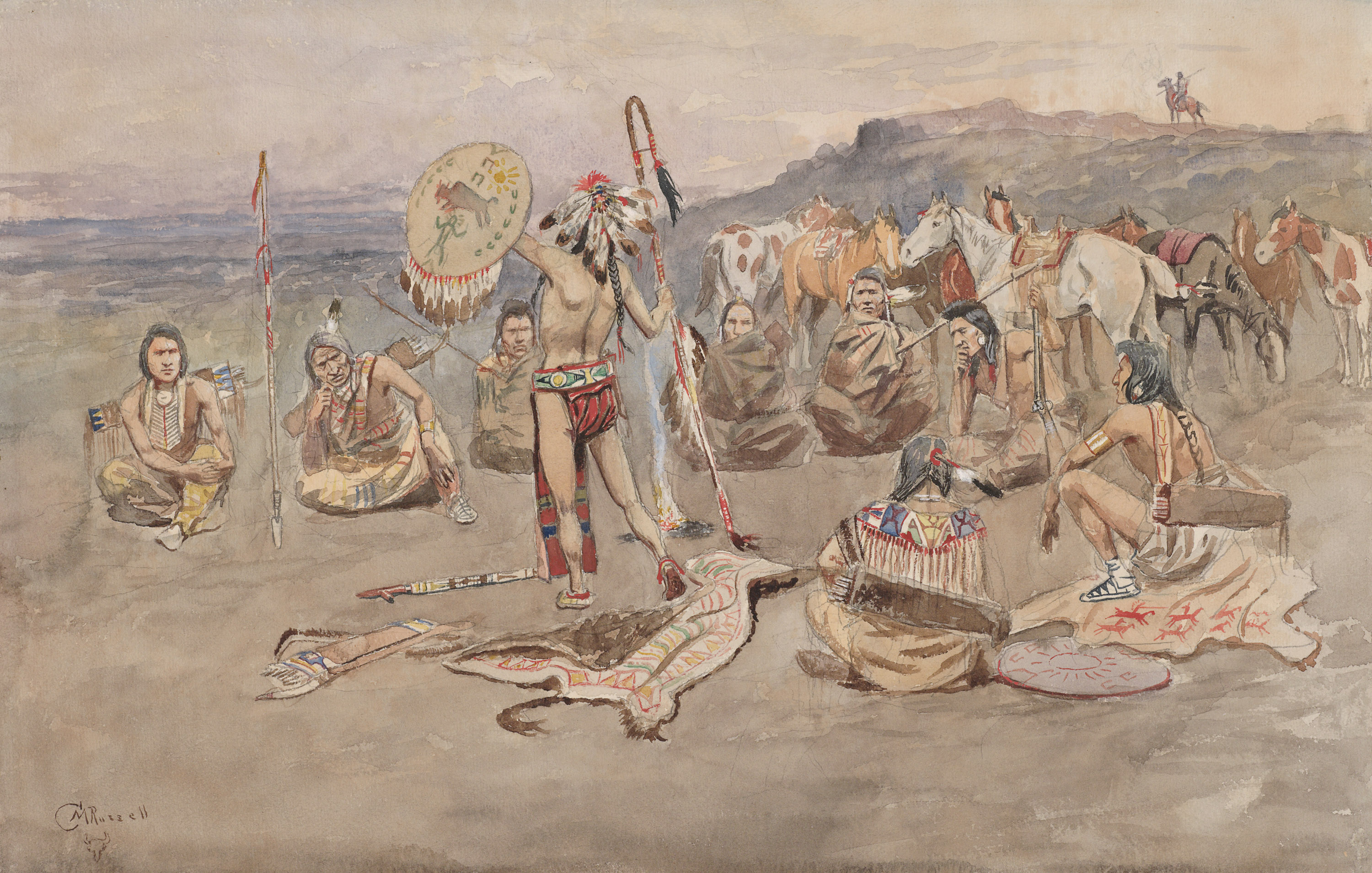

It is especially curious, then, that very few of the contemporary Native-made gifts received by Russell made their way into the artist’s paintings. Instead, he preferred to incorporate objects that, in the eyes of Euro-American audiences, functioned as quintessential emblems of Native American male identity, such as eagle-feather war bonnets, shields, coup sticks, and lances. However, as Russell would soon come to find, accessing and obtaining these objects, many of which carried deep individual significance, proved much more difficult than securing objects created for commercial or reciprocal use. Russell’s ability to acquire these personal items during his brief visits to reservations was limited, presenting a challenge for an artist who relied heavily on studio props.

Russell’s solution was to make his own men’s ceremonial and leadership items. The existing studio collection includes various items altered or wholly fabricated by the artist in the 1890s, including a woman’s cotton dress, a red pipestone tobacco pipe bearing painted designs, and several hide paintings. One of the studio props fabricated by Russell and featured in many of his Native warfare paintings is a fur-and-wool-wrapped wooden staff that De Yong called a “coupe stick,” a rod used to touch, or count coup on, enemies in warfare or to symbolize this act during ceremonies (fig. 2.12). Russell fitted the wooden staff with a sharp steel blade at one end and decorated it with eagle feathers and an imitation scalp made of horsehair toward the opposite, curved end.25 He may have modeled this object after a woodcut illustration of a hooked staff published in Prince Maximilian zu Wied’s Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832 to 1834), which identified the staff as belonging to a member of the men’s Siksika Kit Fox Society.26 Russell could have also seen an example of a much smaller coup stick collected by his contemporary George Bird Grinnell from the widow of the Piikani chief Three Suns. 27 Russell’s imaginative amalgamation of a coup stick and a society lance rendered this object rather ambiguous, capable of serving multiple purposes in the artist’s studio, none of which bore any meaningful relationship to actual ceremonial practices. In The Medicine Man the staff emblematizes the spiritual power and leadership of the central rider (fig. 2.13). Russell wrote of this painting, “The Medicine man among the Plains Indians often had more to do with the movements of his people than the chief and is supposed to have the power to speak with spirits and animals.”28 The staff plays a similar role in his painting War Council, in which it is one of several prominently placed objects signifying leadership (fig. 2.14).

One especially perplexing creation of Russell’s is a composite buffalo-horn war bonnet featuring elements reminiscent of Northern Plains–style feather headdresses and horned bonnets with imaginative embellishments (fig. 2.15).29 Russell attached the tail feathers of an immature bald eagle, the traditional choice of feathers for such headdresses, to a yellow cotton trailer designed to hang vertically down the wearer’s back. The headdress’s cap was crafted from the body of a golden eagle, to which Russell loosely affixed two powder horns to resemble the distinctive Northern Plains split-horned bonnets. A crest of red-dyed horsehair juts out from a striped beaded headband. Russell could have repurposed the bonnet’s components from other Native-made objects so that, in a highly stylized sense, it resembles an object of great power. Russell conveyed this effect in his 1897 watercolor Approach of the White Men (fig. 2.16). The central figure wears the extravagant headgear inspired by Russell’s studio prop, which sways in the wind as the warrior turns his gaze toward the viewer and the approaching group of White men. Russell’s painterly brushwork softens the ethnographic incongruities of the physical artifact, drawing the viewer’s attention to the bonnet’s purpose within the unfolding narrative: an accomplished war leader assessing the impending danger of the encounter.

Russell, like many artists rooted in European painting traditions, relied on costumes, props, and staged settings to produce paintings at a steady pace in his studio. But when he made garments and headdresses for this purpose, even wearing this regalia himself, his practice became entangled with a longer history of cultural appropriation. This behavior was part of what Philip J. Deloria has described as “playing Indian,” a still-common, disrespectful act of adopting Native American culture by dressing up in customary garments.30 Numerous photographs document the overlap between Russell’s Indian persona and his painting practice, such as one in which he confidently sports the headdress (fig. 2.17), but in fact only a select few individuals are entitled to wear such a prestigious item. Headdresses are steeped in symbolism, recounting a specific person’s war honors or society memberships, and must be earned. Proper protocols govern the care of these powerful instruments of protection, and elaborate ceremonies facilitate the transfer of these objects from one individual to another.31 A war bonnet was not the kind of personal item that would have been given away or sold to an infrequent visitor like Russell.32 The artist’s casual appropriation of Native cultural items is particularly problematic in light of the cultural oppression faced by Native peoples during the same era. While Russell and friends playfully and performatively donned Native garments, outright ceremonial bans forced the making and wearing of customary garments underground, and many Native people sold their cultural belongings simply to survive. The communal and spiritual harms caused by this severance from cultural belongings continue to impact Native peoples today.

Conclusion

Charles Russell’s art and personal collection embody a profound tension between the social life of reciprocity, expressed through material culture, and his portrayal of Indigenous people and their cultural belongings in his paintings. In a condolence letter to Nancy Russell upon her husband’s death, Young Boy expressed his deep affection for Charles, remarking, “I sure think of him and feel sorry for him just like my own relation.”33 Nearly a century later, Pearl Raining Bird Whitford reflected on her grandfather Young Boy’s connection with Russell. She noted that the artist displayed genuine kindness and understanding of Indigenous cultures during summertime visits to Native communities in Montana.34 These relationships suggest that Russell’s interpersonal respect may have exceeded that of many of his contemporaries. But personal rapport is not the same as cultural understanding, and these personal ties did not necessarily manifest in Russell’s paintings. His artistic representations of Native culture often flatten Native experiences, strip cultural belongings of their meanings, and evince generalized, romanticized visions of Indigenous life.

Despite this, by nature of collecting, picturing, and creating Native art, Russell emerged as a trusted interpreter of Native culture to the wider public. He even served as the judge for the “Indian Wardrobe and Equipment” competition category at the 1919 Calgary Stampede, a celebrated rodeo and exhibition of western culture.35 His role in shaping public perceptions was amplified by his success in popularizing western Montana as a destination for picturing Native people and collecting their belongings.36

How do we reconcile this contradictory legacy? A crucial insight lies in understanding that within Native art, kinship and creativity are inherently intertwined. This perspective is vital when examining the Native-made cultural belongings in Russell’s collection, especially those gifts that Russell chose not to depict. The cultural belongings in his collection, when considered on their own terms, can highlight Native artistic transformations within a context marked by complex and often unexpected circumstances. This essay marks an initial step toward a fuller understanding of the Native artists who were contemporaries of Russell. The next phase of research must adopt a more reciprocal approach, involving contemporary Native artists and the descendants of Russell’s Native acquaintances directly in the scholarship. This collaborative effort is vital for developing a deeper, more nuanced understanding of Russell’s legacy and ensuring that the interpretations of his work are informed by those who are most connected to the stories he depicted.

Endnotes

-

I am incredibly grateful for the generosity and insights into Russell’s practice and relationship to Native people shared by Sarah Adcock, Renee Bear Medicine, Heather Caverhill, David Dragonfly, Aaron LaFromboise, Dana Turvey, Louis Still Smoking, and Cheryle Zwang. ↩︎

-

Jodie Utter, “Russell’s Studio Practice: The Flood Collection,” in The C. M. Russell House and Studio (Great Falls, MT: C. M. Russell Museum, 2019), digital publication, accessed January 14, 2025. ↩︎

-

A few Asian- and African-made objects are also listed. Curiously, several items that appear in photographs of Russell’s studio taken before the artist’s death do not appear in the De Yong inventory or the C. M. Russell Museum’s digital database. ↩︎

-

On the influence of Karl Bodmer and George Catlin on Russell, see John C. Ewers, “Russell’s Indians,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 37, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 36−53; and Anne Morand, “Charles M. Russell: Creative Sources of a Young Artist Painting the Old West,” in The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell: A Retrospective of Paintings and Sculpture, ed. Joan Carpenter Troccoli (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 129−51. ↩︎

-

Items of this kind appear in photographs of Russell’s studio. The Piikani backrest could be no. 27 in De Yong’s inventory, “back rest of willow poles,” and the beaded buckskin dress is likely no. 69 in the inventory. ↩︎

-

The C. M. Russell Museum’s records credit Russell as the maker of this object, but it appears to be authentic and made during the late nineteenth century when buffalo hide was still accessible. De Yong called the container a “medicine bag” in his inventory (no. 78), though rectangular containers of this size did not have a ceremonial use. ↩︎

-

While some have claimed that Russell resided in a tipi for six months and was adopted into the tribe during this period, Hugh A. Dempsey, after meticulously examining historical records and Kainai oral histories, dispelled these myths. Hugh A. Dempsey, “Tracking C. M. Russell in Canada, 1888−1889,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 39, no. 3 (Summer 1989): 2−15. ↩︎

-

It is possible that Russell met the Methodist minister Reverend John Maclean, who established a Christian mission at Fort Macleod in 1880 and worked extensively with Kainai bands. MacLean’s efforts to build relationships with Kainai elders and learn their language over the course of a decade drew the attention of ethnologists in England, Canada, and the United States, who encouraged him to collect artifacts. See Arni Brownstone, “Reverend John Maclean and the Bloods,” American Indian Art Magazine (Summer 2008): 44−107. ↩︎

-

Jessa Rae Growing Thunder, “Hi-Line Treasures,” Native American Art Magazine 38 (April/May 2022): 92−97. ↩︎

-

“Sun Dance Fort Belknap,” Great Falls Tribune, July 2, 1904. ↩︎

-

“To Open Many Acres to Settlement by Whites,” Great Falls Tribune, September 4, 1905, p. 5. ↩︎

-

The Fort Belknap tribes’ battle over Milk River water rights in 1905 received wide coverage in Montana newspapers. In 1908, the United States Supreme Court case Winters v. United States recognized the water rights of Native people on the reservation. ↩︎

-

Joe D. Horse Capture, conversation with the author, September 25, 2023. See also Joe D. Horse Capture, George P. Horse Capture, and Sean Chandler, From Our Ancestors: Art of the White Clay People (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2009). ↩︎

-

Sumner W. Matteson, “The Fourth of July Celebration at Fort Belknap,” Pacific Monthly 16, no. 1 (July 1906): 94−103. ↩︎

-

Mitchell A. Wilder to Mrs. J. Lee Johnson III, September 30, 1964, Big Bear File, Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. ↩︎

-

George P. Horse Capture, “Memories of Charles M. Russell among My Indian Relatives,” in Troccoli, The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell, 127. ↩︎

-

John G. Carter, “Fort Belknap Notes, Atsina Indians, Book 5” (typescript, 1909), 302−3, box 1, John G. Carter Papers, Montana State University Library, Bozeman; also mentioned in Horse Capture, “Memories,” 125. ↩︎

-

Celeste River, “Mountain in His Memory: Frank Bird Linderman, His Role in Acquiring the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation for the Montana Chippewa and Cree, and the Importance of the Experience in the Development of His Literary Career” (master’s thesis, University of Montana, 1990), 118−19. ↩︎

-

Larry Burt, “Nowhere Left to Go: Montana’s Crees, Metis, and Chippewas and the Creation of Rocky Boy’s Reservation,” Great Plains Quarterly 7, no. 3 (Summer 1987): 195−209. ↩︎

-

De Yong gave Russell nêhiyaw items that he collected after the establishment of Rocky Boy’s Reservation, including a dog travois made by Billie Small (no. 32) and a wooden horse-head mirror made by Flying Bird (no. 51). ↩︎

-

De Yong also noted a gift from Buffalo Coat of “Eagle Medicine,” no. 11 in the inventory, though he did not specify what this item was. ↩︎

-

Friend Young Boy, March 1, 1902, Gilcrease Museum, 02.1584, accessed December 17, 2024. ↩︎

-

De Yong inventory, no. 87. ↩︎

-

De Yong inventory, nos. 43 and 67. ↩︎

-

De Yong inventory, no. 140. ↩︎

-

Maximilian zu Wied, Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (Koblenz: J. Hoelscher, 1839), 577. ↩︎

-

Currently in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian. ↩︎

-

C. M. Russell to Willis Sharpe Kilmer, April 24, 1911, Rick Stewart: Personal Research Collection, CMR: Letters, E–K, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives. ↩︎

-

This object is likely no. 68, “Eagle and Buffalo Horn War Bonnet,” in De Yong’s inventory. De Yong did not indicate whether Russell made this item, as he did with other objects fabricated by Russell. ↩︎

-

Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998). ↩︎

-

Clark Wissler, “Ceremonial Bundles of the Blackfoot Indians,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History 7, pt. 2 (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1912), 114−16. ↩︎

-

Frank Bird Linderman, an author and ethnologist who worked extensively with Hi-Line communities, collected war bonnets, eagle-wing feather fans, and numerous examples of beadwork. Linderman documented the provenance of these items, especially those with sacred or societal symbolism. See Billie G. Kelly, “Frank Bird Linderman Collection: A Study in Historic Material Culture” (master’s thesis, University of Montana, 1984). ↩︎

-

Mr. John Young Boy to Nancy Russell, December 5, 1926 [C.7.12], folder CMR/BC/C.7.10–C.7.19, Rick Stewart: Charles M. Russell Projects—Britzman Collection Photocopies, Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives. ↩︎

-

C. M. Russell Museum, “Russell in Perspective—Young Boy,” educational video, September 21, 2022, accessed December 17, 2024. ↩︎

-

“World’s Greatest Stampede Began This Afternoon,” Calgary Herald, August 25, 1919, p. 16. ↩︎

-

Joe Scheuerle and Maynard Dixon were among the many artists who visited Russell’s Bull Head Lodge on Lake McDonald in Glacier National Park and painted Piikani subjects. See Jennifer Bottomly-O’looney, “Sitting Proud: The Indian Portraits of Joseph Scheuerle,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 58, no. 3 (Autumn 2008): 64−72; and Donald J. Hagerty, “Where the Prairie Ends and the Sky Begins: Maynard Dixon in Montana,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 60, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 24−41, 94−95. ↩︎