Early in his career as an artist, Charles Russell visited the A’aninin elder Horse Capture at the Fort Belknap Reservation. According to Horse Capture’s great-grandson George P. Horse Capture Sr., Russell “would visit in the hot summer and they would sit together on the northern side of the house where it is coolest, and sign-talk with each other. Russell was quite good at sign-talking. They would spend hours there smoking, talking, laughing and telling old stories.”1 Horse Capture Sr. also recounted a story about another Gros Ventre elder, Ice, known as Bill Jones Son of a Bitch. It was common knowledge in the area that Russell frequented Gros Ventre and Blackfeet country. One day when Russell was riding on the reservation, it began to rain, so he stopped at a lodge, announcing himself at the door. Bill, the owner of the lodge, welcomed Russell in, and the two men greeted one another. Russell had brought with him a box of art supplies and started painting to pass the time during the rain. He created a portrait of Bill, and once he’d finished it, Bill examined the painting. He signed to Russell about his braided hair on the left side in the painting, where Russell had depicted only three beads. Bill then signed and showed Russell that his braided hair actually had five beads on the left side. Russell fixed the painting and gifted it to the elder. When the rain stopped, Russell mounted his horse and departed. A year later, when Russell came to visit again, Bill presented the artist with a gift to show his gratitude.2

As Horse Capture Sr.’s stories indicate, Hand Talk, now referred to as Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), played a significant role in Plains Native Americans’ communication systems when Russell resided in Montana.3 The tribes Russell interacted with in Montana included bands of the Blackfeet Confederacy, including Blackfeet (Aamskapi Piikani), Blackfoot (Niitsitapi or Siksikaitsitapi), Blood (Káínaa), and Piegan (Piikani), as well as the Assiniboine/Nakoda (əˈsɪnɪbɔɪnz or Asiniibwaan), Cree (nêhiraw, nêhiyaw, or nêhirawisiw), Crow (Apsáalooke), Gros Ventre (A’aninin), Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa, Sarcee (Tsúùtínà), and Stoney (Îyârhe Nakoda). Russell learned Hand Talk from these peoples and used it to communicate with them when he visited their reservations in the United States and Canada.4 Sign language had by then been intergenerationally transmitted within tribes for centuries. While the Plains Indians of the past faithfully preserved it, PISL is rarely seen in use today. Recent generations are not as fluent as their elders were, and the last of the fluent signers are in their late sixties and older. PISL was commonly used among tribes for communication and other purposes, especially as many Native elders did not know English.

Although several artists from Russell’s era, including Winold Reiss, incorporated PISL into their pictures, Russell was unique among artists of the American West in the attention he gave to the language. Not only did he portray individual signs, but he also offered a glimpse of the social world of PISL—the many ways that it was used within Plains communities. His artwork—a combination of sign-language documentation, landscape, action, and storytelling—fascinates me for how it presents the world of PISL within Russell’s time. PISL, it is important to note, is not a universal language. It is a regional language variety of North American Indian Sign Language (other varieties include Southwest Indian Sign Language and Northwest Indian Sign Language). Additionally, while certain signs are shared across communities, individual tribes have their own culturally specific signs, which they use within their communities but not outside of them. Two tribes may live on neighboring reservations but use different signs to communicate the same idea. For instance, Blood signers of the Northern Plains have different signs for certain concepts when compared to the Kiowa of the Southern Plains. Such differences are based on specific cultural contexts related to ceremonial practices, foods, clothes, culturally designed beadwork, and things that are used in traditional ways. Those who have studied PISL and its language varieties have provided evidence that it is not a universal sign language, as previously claimed in much PISL literature, which often has been written by non-linguists, non-Native authors, and tourists, many of whom have at best a limited understanding of PISL signs sourced from secondary and tertiary sources, and who rarely socialized with actual Hand Talkers to fully understand their signs, way of communication, and culture. Some PISL signs, though, are shared across multiple communities of Hand Talkers. These shared signs are the ones that appear predominantly in Russell’s paintings.

Linguistic Description of PISL

When researching PISL signs, I conduct phonological documentation. This type of analysis is based not on sound but instead on signs and movement. Specifically, I study the five phonological parameters of signed languages: handshape, location, movement, palm orientation, and non-manual markers (such as facial expressions). I document these features as they appear in images of signs, and then I share them with fluent PISL signers. There are limits to this approach, however, when studying Russell’s depictions of sign language. When analyzing paintings, it is hard to identify signs because of the lack of movement of the hands when displaying a sign, which in the field are called “common signs in the immovable movement.” Put another way, imagine seeing a drawing or a painting of a person making an “E” sound. This could signify different words, like escape, exciting, or eager. But how would you know which word is being uttered in the picture? The same principle is at play with the signs in most of Russell’s paintings. Russell himself was aware of this fact. He once explained, “I have tryed [sic] sometimes in my pictures to make Indians talk sign, but it is hard to make signs with out [sic] motion.” Some signs are identifiable, but others are vague. To further complicate matters, there is also the possibility that a depicted sign belongs to a specific tribe and is not necessarily within the known lexical list of PISL.

For example, consider the sign LOOK, which is represented by a V handshape pointing to where the eyes are looking.6 Depending on the direction in which the hands move, it would be interpreted as LOOK-right or LOOK-left, and so on. It could mean “look over in this direction.” The sign for LOOK-direction can differ; for clear understanding, it is critical to see the direction of the hands to tell which cardinal direction the sign is pointing to. Furthermore, with the same V handshape, if the sign is dragging sideways, it can mean DOG instead of LOOK. Take a few examples of the same V handshape: It could mean LOOK, DOG, LIE DOWN, FALL DOWN, or LOOK-over-there, but the hand movements are all slightly different. In a static representation in a painting, such hand movements are nonexistent. With this in mind, the PISL signers I engaged studied with me the story or description of each drawing and painting I selected, including landscape, materials, props, and clothes, to gain contextual information that would help us identify the signs Russell employed. Even if a depicted sign is impossible to definitively identify, Russell’s paintings still tell us useful things about PISL in Plains communities.

According to Russell’s student and close friend, the painter Joe De Yong, Russell frequently performed PISL for friends and colleagues, as well as with Native Americans. In one instance, he performed a PISL skit for Howard Eaton and his ranch hands at Bull Head Lodge, Russell’s residence in what is today Glacier National Park. Such audiences were led to believe Russell was fluent in sign language, but in fact these performances were prepared beforehand in order to entertain visitors. Russell would typically memorize signs, and his wife, Nancy, would translate the performance. Their routine was “scripted and rehearsed,” according to Russell biographer John Taliaferro, copied from “hotel-lobby Indians.”7 I came to this conclusion as well after I observed the only existing original film, housed at the Montana Historical Society, showing Russell signing in PISL. He does not have accurate movements when signing, like fluent PISL signers usually do, and he holds his hands after each sign, which is uncommon among historical traditional signers. Given that Russell was a late learner of PISL, he was not fluent in sign-language movements and handshapes like those used by PISL signers. While he was clearly able to carry on normal conversations in PISL, the old film shows the selective signs that he knew.8 That said, one film is not necessarily enough to confirm his lack of fluency in signing; he may have been nervous or uncomfortable signing in front of the camera. But there is no substantial evidence that Russell could converse fluently with the ability of authentic Hand Talkers.

Many accounts of Russell’s knowledge and use of PISL come from De Yong, who was Russell’s protégé. At age eighteen, De Yong lost his hearing from spinal meningitis, a common cause of deafness. De Yong did not learn American Sign Language from any deaf person, and he made no mention in his journals of meeting another non-Native deaf person; instead, De Yong had early exposure to PISL while living in Dewey, Oklahoma, where he learned it from the Delaware, Cherokee, and Osage residing there after the territory became a state.9 De Yong had a collection of 900 signs he learned when he was in Oklahoma, commenting that he used Hand Talk in a “day-by-day way” such that “thinking in signs became second nature.”10

De Yong’s knowledge of Hand Talk became still more useful once he moved to Montana and interacted with tribal elders in Great Falls and while traveling with the Piegan and Blackfeet tribes; he called those who taught him more signs “Reservation Indians.”11 He became close with Russell’s friend John L. Clarke, a well-known deaf Blackfeet woodcarver and painter based just outside of Glacier National Park; they remained friends for over fifty years.12 Clarke and De Yong bonded because of their shared interest in Hand Talk, with the latter writing that they not only used what he called Sign Talk but also communicated “either by word-of-mouth or Sign Talk or, sometimes if I failed to get his exact meaning, by writing.”13

Hand Talk in Russell’s Art

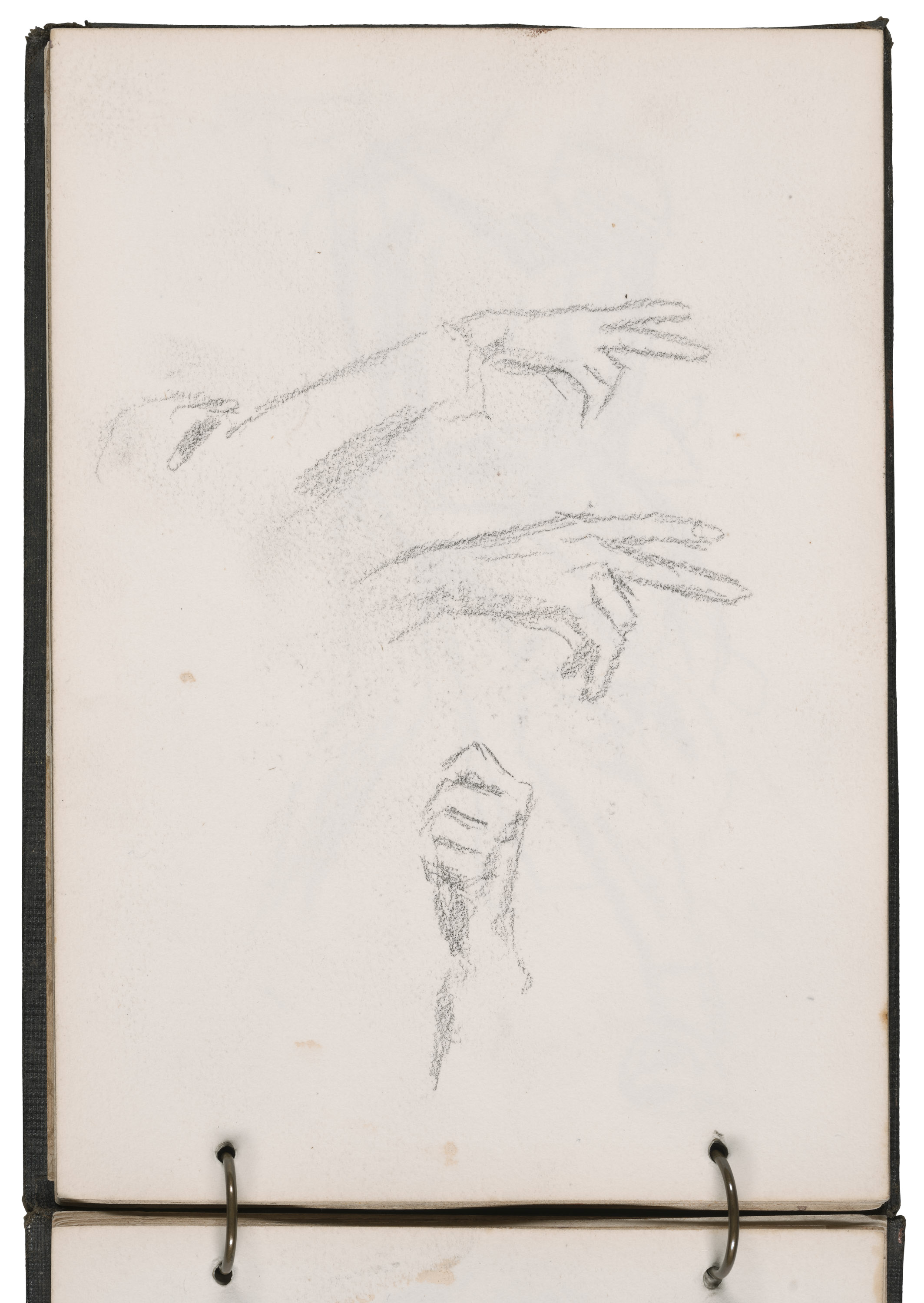

For Russell, Hand Talk and the Native characters in his paintings had to go together to understand the true meaning of the American West. This is what fascinates me; his works give a contextualized whole, not just parts, as in PISL dictionaries. Turning to Russell’s artworks, I begin with Russell’s V handshape, which appears in one of the many sketches of hands that he drew as a way of practicing his depiction of signs (fig. 4.1). This V handshape, pointing sideways and downward, is the sign for LOOK. The fist handshape is a sign meaning SIT and HERE.

Russell used the sign for LOOK in several of his paintings, including The Medicine Man (fig. 4.2). The painting shows numerous Native Americans on horseback, and the rider at the far left, his arm silhouetted against the sky, makes a LOOK sign, which could mean “look over there in the distance” or “look at that” or “watch.” A similar LOOK sign is depicted in The Silk Robe (fig. 4.3). In this instance, the man seated at center is using the sign, perhaps while telling a story about the dog in the left middle ground or directing someone to look at the work of the woman who toils over a bison hide to produce a robe.14

In Lost in a Snowstorm – We Are Friends (fig. 4.4), the sign for HORSE is featured prominently near the center of the canvas. This HORSE sign can represent a verb, like RIDE, or a noun, such as HORSE, so the signing figure could be communicating “I am on a horse” or “I need a horse.” As a verb, the sign could mean “I have been riding for days or hours” or “he rode that way.” A letter in the Amon Carter Museum of American Art’s archives written by L. H. Floyd-Jones, a Montanan who was the original owner of this painting, speaks to the sign in this work. He addressed the letter to T. M. Markley of St. Louis, the second owner of the painting. Floyd-Jones explained, “I am informed by Miss Helen P. Clarke who is of Indian blood—is a descendent [sic] of the explorer Clark of the famous expedition of Lewis and Clark that this county is named after.”15 He continued: “The sign means, ‘on horseback crossing the divide, or back-bone of a range of mountains.’ The cow-boys are lost from their party and have asked the indians [sic] the whereabouts of their party, and this is the indians reply.”16 While Floyd-Jones’s letter provides a possible explanation for the painting’s Hand Talk, it does not fully reflect the specifics of the sign HORSE.

Russell’s drawing Indians Meet First Wagon Train West of Mississippi (fig. 4.5) captures a male Native American in an interesting pose—the Hand Talker appears to be looking directly at the viewer, while all the other subjects’ heads are turned toward the newcomers in a long train of covered wagons and horses. One wonders if Russell drew this figure to make it appear as if he were conversing with the viewer in sign. Or perhaps the subject is signing to an unidentified companion somewhere outside the composition. To learn more about this sign, I consulted a Northern Cheyenne signer, who agreed that the sign appears to be the Cheyenne (as well as Kiowa) sign for BRAVE, WOW, or TOUGH. Another possibility, per a Pawnee signer I consulted, is that the sign could mean SCALP or “wow, many scalps to collect.” But we can’t be certain which sign is being used as it depends on the context of the conversation the Hand Talker is having, either with Russell or with someone else. We are also limited in discerning the full meaning of the scene due to the lack of movement of the signer’s hands. The best educated guess is the idea of “wow, there are many wagons” or “they are brave to come to Indian Country.” Here, Russell’s portrayal does not allow for a definitive identification of the sign.

In another of Russell’s drawings from around the same time, Bent’s Fort on Arkansas River (fig. 4.6), the artist depicted a fort that belonged to William Bent, Russell’s grandmother Lucy Bent’s brother. William and his brother Charles were famous traders who traveled and wintered with other trappers and traders in Wyoming. In 1833, the two brothers built Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River in collaboration with the French trader Ceran St. Vrain; the historian James P. Ronda notes that “building Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River made the brothers powerful players in a complex world of trade, diplomacy, and imperial expansion.”17 Their adobe fort was a stronghold for trading. In Russell’s drawing, a male Native sits astride his horse at the front gate of the fort and signs BUY/SELL to the fort’s watchman. He is accompanied by his wife and son on horseback, along with packhorses laden with fur goods intended for sale to the trading-post owner at the fort.

Russell’s painting The Wolfer’s Camp (fig. 4.7) depicts a business that was very popular across the United States and Canada in the late 1800s. Wolfers made a great deal of money, with one skinned wolf pelt selling for as much as two dollars.18 Wolfers were called upon to hunt and bait wolves in the Midwest and the Great Plains. They used strychnine-poisoned carcasses of bison, elk, deer, and other animals, leaving them on the plains for the wolves to eat. The wolfers would return the next day, or after winter was over, to find dead wolves ready for skinning. From 1870 to 1877, an estimated 55,000 wolves were killed for bounty money in Montana, and by 1911, the Montana wolf was nearing extinction except in the northern parts of the state.19 According to historian Doris Jeanne MacKinnon, people of the time “judged wolfers to be a grade lower than the whiskey and Indian traders . . . not a very outstanding class of men in the history of Alberta,” adding that 90 percent of buffalo hunters became wolfers for the income.20 Russell must have met wolfers during his Montana residency, as wolfers and buffalo hunters were everywhere in Montana. In this snowy landscape, Russell depicted wolfers communicating with a Native man whose family stands behind him. Just to the left of the burning campfire, somewhat occluded by smoke, sits a white sack marked “XXX,” likely strychnine; wolf pelts hang on a line behind the seated figure, identifying the campers as wolfers. According to a Blackfeet Hand Talker I consulted, it appears the Blackfeet man is making a compound sign (two signs combined for one concept), in this case CAPTURE and GIVE.

Russell’s painting Crow Indians Hunting Elk (fig. 4.8) depicts another sign: a hand held out, meaning WAIT. It is well known that Hand Talk was and is used during hunting and war because it allows for silent communication. This painting shows two Crow warriors hunting for elk, waiting quietly before taking their shot. Today, the sign WAIT remains in use, though for different purposes, like WAIT-for-me, WAIT-in-line, or WAIT-here. This same sign is employed in Russell’s oil paintings Indian Scouting Party (fig. 4.9) and Crees Meeting Traders (fig. 4.10). In Euro-American ideologies, there is a common misconception involving Native people holding up a hand and saying, “How.” This erroneous interpretation was bolstered during the early days of Hollywood, when westerns did not accurately reflect the usage of this sign. According to practicing Hand Talkers, a sign like this carries multiple possible meanings: to indicate that a group should stop riding and stand side by side or in a line; as a greeting; to indicate to others to slow down; to say “I come in peace” or “good to see you”; or to inform an opponent that they are arriving to the location of a meeting place. In Russell’s pictures, seemingly simple gestures contain a wealth of complexity.

Although it is not always possible to identify specific signs in Russell’s pictures, his attentiveness to the importance of Hand Talk is apparent, as in his wonderful watercolor Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia (fig. 4.11). Russell’s portrayal is exceptional in that it features a Native woman Hand Talker so prominently. Many have unfairly dismissed Sacajawea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who was a guide for Lewis and Clark; such writers fail to recognize that Sacajawea played multiple important roles during the expedition: serving as a guide, interpreter, and nurse; gathering food and securing horses; and allaying suspicions of approaching Native Americans through her presence—a woman and child (Sacajawea’s son, Jean Baptiste) accompanying a party of men indicated peaceful intentions. When one of the expedition’s pirogues nearly capsized, it was Sacajawea who managed to save many valuable supplies, “almost every article indispensably necessary to . . . insure [sic] the success of the enterprise,” according to William Clark’s journal entry for that day.21 Russell, perhaps in recognition of Sacajawea’s immense value to the expedition, placed her in the center of this composition. His painting focuses largely on her. All the males in the surrounding canoes remain silent and motionless as they give full attention to Sacajawea.

Most western artists do not give Native female interpreters the praise or recognition they deserve. Ronda observes of this picture, “Sacagawea stands in the bow of a crude expedition canoe offering signs of peace and friendship,” though he also points out that “if Sacagawea played any role in the meeting, it went unrecorded” in Lewis and Clark’s journals. Yet Russell’s painting depicts her as a pivotal mediator between the two cultures, her presence confirming that the group was not a war party.22 She appears to be signing APPROACH, meaning “we are approaching by canoe.” Again, though, one sign is not enough to convey her full message; it could mean “we are approaching you in a very peaceful way,” or “we are approaching your territory.” These are the most likely potential meanings based on PISL signers’ observations and contextual clues within the painting.

Charles Russell created many impressive depictions of PISL over the course of his career. Indeed, his contribution to preserving the language is remarkable. One will not find many cowboy artists who depicted Hand Talk so extensively. Most authors of PISL dictionaries used only sketches or pictures, or even no pictures at all, with English descriptions of the signs. In my mind, Russell preserved PISL far better, crafting his documentation with stories, landscapes, and other images. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words—or, in this case, signs.

Endnotes

-

George P. Horse Capture Sr., “Memories of Charles M. Russell among My Indian Relatives,” in The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell: A Retrospective of Paintings and Sculpture, ed. Joan Carpenter Troccoli (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 123. ↩︎

-

Horse Capture Sr., “Memories of Charles M. Russell among My Indian Relatives,” 124−25. ↩︎

-

The term “Hand Talk” was used commonly during Russell’s time. “Plains Indian Sign Language,” or “PISL,” is the term now used within the field of linguistics, and this updated terminology has spread in Native communities today. The terms “Hand Talk” and “Plains Indian Sign Language” are used interchangeably, and both are acceptable. ↩︎

-

Biographer John Taliaferro notes that Phil Weinard, a cowboy and part-time vaudevillian who traveled with Russell, taught the artist some Hand Talk, but “his vocabulary was still rudimentary, at best.” John Taliaferro, Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist (Boston: Little, Brown, 1996), 78. George P. Horse Capture Sr. notes, though, that when Russell visited Horse Capture on the reservation, “Russell was quite good at sign-talking.” Horse Capture Sr., “Memories of Charles M. Russell among My Indian Relatives,” 123. ↩︎

-

Charles Russell to William Tomkins, May 27, 1926, in Charles M. Russell, Word Painter: Letters 1887–1926, ed. Brian W. Dippie (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993), 392. ↩︎

-

Signs in the linguistics of sign language are documented in capitalized letters. ↩︎

-

Taliaferro, Charles M. Russell, 211−12. Today, playing or imitating “Indians,” including the use of Hand Talk, is considered a disrespectful offense by many Native peoples. Hand Talk is considered sacred by most Native practitioners, and its use and imitation by non-Natives is considered cultural appropriation. ↩︎

-

Horse Capture Sr., “Memories of Charles M. Russell among My Indian Relatives,” 123. ↩︎

-

J. A. G., ed., “Joe De Yong, Artist,” Volta Review 24, no. 2 (February 1922): 39−44. ↩︎

-

Brian W. Dippie et al., Charlie Russell and Friends (Denver: Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum, 2010), 49. ↩︎

-

J. A. G., “Joe De Yong, Artist,” 40. ↩︎

-

Larry Len Peterson, Blackfeet John L. Cutapuis Clarke and the Silent Call of Glacier National Park: America’s Wood Sculptor (Helena, MT: Sweetgrass Books, 2020), 97. ↩︎

-

Joe De Yong, “Charlie and Me . . . We Run Together Fine,” Remembering Russell’s West 1, no. 2 (1993), accessed April 12, 2024. ↩︎

-

With most tribes, storytelling happened between the first and last frost, during winter and inside tipis, so this painting does not match the culture of the Plains Indians. However, Russell’s painting may portray a more casual visit between two elderly men rather than a formal storytelling. ↩︎

-

Helen Piotopowaka Clarke (1846−1923) was an actress, educator, and bureaucrat who had a mixed heritage of Piegan Blackfeet and Scottish American. Contrary to what Floyd-Jones wrote in his letter, she was not related to Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition. ↩︎

-

L. H. Floyd-Jones to T. M. Markley, June 1, 1900, Lost in a Snowstorm – We Are Friends object file, Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. ↩︎

-

James P. Ronda, “Charlie Russell Discovers Lewis and Clark,” in Troccoli, The Masterworks of Charles M. Russell, 197. ↩︎

-

For more on the wolfing business, see Jim Yuskavitch, In Wolf Country: The Power and Politics in Reintroduction (Guildford, CT: Lyon Press, 2015); Michael Wise, “Killing Montana’s Wolves: Stockgrowers, Bounty Bills, and the Uncertain Distinction between Predators and Producers,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 63, no. 4 (Winter 2013): 51−67, 95−96; and Phyllis Smith, “Killing Fields,” Outside Bozeman (Winter 2000−01), accessed September 18, 2024. ↩︎

-

Smith, “Killing Fields.” ↩︎

-

Doris Jeanne MacKinnon, Metis Pioneers: Marie Rose Delorme Smith and Isabella Clark Hardisty Lougheed (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2018), 294. ↩︎

-

Grace Raymond Hebard, Sacajawea: Guide of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Glendale, CA: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1933), 52. ↩︎

-

Ronda, “Charlie Russell Discovers Lewis and Clark,” 201. ↩︎