Among the things that Charles Russell hated, cars were near the top of the list. Trains, too. Anything not powered by muscle roused his ire, which he freely expressed in correspondence with family and friends, and only a bit guardedly in public forums. In an interview with the New York Times, he fumed, “If I had my way I’d put steam out of business,” unaware that in a scant few years steam would, in fact, be supplanted by something he disliked more—the gasoline engine.1 Many ironies accompanied his torment, of course. His career relied on the seamless transitions provided by a modern rail network to transport him and his work to exhibitions around the country. He steamed across the Atlantic on the Lusitania a year before its sinking, and the luxury cars that his wife, Nancy, owned carried the family between their homes in Great Falls and Lake McDonald and, eventually, the beaches, orange groves, and film lots of Southern California, where they resettled a year before Russell’s passing.

Moreover, the fortunes that funded his endeavors largely emerged from these revolutions in mobility. Money from industrial oil, steel, and rubber exchanged for paintings and sculptures of sinew and flesh provided a material basis for Russell’s pieces alongside his ink, paint, and bronze. But a luddite nostalgia effacing the industrial origins of this wealth became Russell’s brand, and he trucked this imagery to a new generation of western art collectors, for whom depictions of animals, particularly buffalo and horses, took on symbolic importance as expressions of muscle power (fig. 5.1).

Throughout Russell’s career, the taut, unpredictable bodies of animals provided aesthetic counterpoints to the sleek lines of the machines remaking modern transportation. For example, in contrast to inanimate, standardized vehicles bolted together by factory workers, horses are individuals, made mobile by their individual owners with unique variations of tack and saddlery, which Russell committed himself to documenting in detail, as in his iconic painting In Without Knocking (fig. 5.2). For Russell, horses were companion animals, but unlike the household pets taking America by storm during his lifetime (the dogs and cats that Russell also despised), the horse was a partner in work, a domestic but not necessarily a dependent, a representation of self-reliance and distance from the emerging economic interdependencies of modern America. In Russell’s hunting and ranching works, the discrete bodies of individual bison, range cattle, and other animals celebrate a self-reliant and direct form of meat-making estranged from the stockyards, slaughterhouses, and shop counters that increasingly provisioned Americans with food from truck-borne cans and refrigerated railcars. Russell’s animal artwork is best understood within the context of his concerns over the Machine Age’s diminution of muscle, notably in terms of transportation but also in relation to the parallel expansions of domestic petkeeping and industrial meat production (fig. 5.3).

Russell’s reliance on animals to assert his reluctance to these modern changes fits within larger patterns of behavior that marked the economic and ecological transformations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.2 In one sense, Russell’s perspectives on these modern transformations fit largely within the patterns of nostalgia established by other men of means during his generation, and Russell scholars have commonly situated the artist and his work within this context. As Brian W. Dippie observes, Russell’s own background as scion of a prominent St. Louis family produced a “contemporary impression of Russell . . . that was akin to that of an English remittance man, spoiled for work by indulgent parents back in the Old Country.”3 As with Theodore Roosevelt, who left Oyster Bay in the 1880s to play cowboy with his aristocratic French friend the Marquis de Morès, Russell’s youthful labors—while not exactly leisurable—were nevertheless optional. At any point he could quit and take a boat back downriver, an alternative not generally available to the working-class men in whose culture he immersed himself. But stopping with an analysis of Russell as another historical example of a bourgeois male seeking out an experience of “authentic” labor on the open range misses a vital economic and social transformation that informed his work: the transformation from horse-drawn to motorized transportation. It also overlooks the genuine affinities (and prejudices) Russell held toward animals, elements of his life that suffused his work.

Manhood, Muscle, and the Wilderness

Russell’s depictions of animals situated his work at the forefront of an emerging tension between automobiles and masculine ideals of how nature should be properly experienced. For those who shared Russell’s sentiments, cars and roads were an unwelcome and emasculating presence in society. They were seen as the main obstacles to the preservation of public lands for “primitive recreation,” a set of activities premised on the expenditure of human and animal muscle power to restore one’s soul in an era of nervous depletion. As Robert Marshall wrote in 1930, just four years after Russell’s death, revitalizing natural spaces required a landscape “possess[ing] no possibility of conveyance by any mechanical means and sufficiently spacious that a person in crossing it must have the experience of sleeping out.”4

By the time the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, Marshall’s proclamations had become sacrosanct. In the hallowed halls of the U.S. Capitol, Senator Frank Church proclaimed that “wilderness begins where the road ends; and if the roads never end, there never will be any wilderness.”5 Midcentury wilderness advocates who were known for their irreverence, such as Edward Abbey, were nevertheless high-handed when it came to the harms allegedly wrought by roads and cars. As the historian Jon T. Coleman aptly described: “According to Abbey, the internal combustion engine was robbing American males of their love of freedom as well as their connection to ‘Mother Earth.’ He advocated banning cars in national parks and forcing tourists to walk, even if this led to them getting lost and perishing. For him, dying bewildered was preferable to living in the sterile confines of an automobile interior.”6 Created a half-century prior, Russell’s visceral paintings and sculptures of horses and other beasts provided an artistic foundation for both contemporary and future expressions of this wilderness ideal as well as the de-machining tendencies of twentieth-century American environmentalism.

For Russell, wilderness was a place where muscle power marked not only the limits of mobility but also the limits of survivability, a place where one had to kill animals to subsist on their flesh as food. His hunting images often depict these contests between man and beast in ways that showcase muscle as a precious resource. Buffalo Hunt [No. 39] (fig. 5.4), for example, depicts Native hunters astride galloping horses circling a herd of bison, the most visible man in the foreground with an arrow drawn and aimed. The musculature of horse and rider is caught in a play of shadows, emphasizing the lean yet well-developed shoulder of the hunter and his mount’s powerful flank.

The scene also evokes tensions between wildness and domestication. The horses belong to the riders, but to whom do the bison belong? In a midcareer masterwork reproduced several times, Russell seemingly answered the question for us. The title of the piece, When the Land Belonged to God, gestures toward its fundamental message: that even in the absence of human ownership, the beasts still belong to someone (fig. 5.5). When one of the canvases served as the centerpiece of Russell patron Malcolm Mackay’s “Charlie Russell Room,” it suggested a view that nature was a convertible asset, a divinely sanctioned form of property, ownership of which God would eventually transfer to settlers.

In fact, it was Russell’s participation in the 1908 roundup and sale of the Flathead Reservation’s bison herd on the eve of the reservation’s allotment that Nancy described as the inspiration for the buffalo-hunt paintings. From 1891 until 1928, efforts to force the privatization of Native landownership guided federal Indian policy in the United States. During these years, approximately two-thirds of tribally owned reservation lands passed into the hands of non-Native landowners, predominantly through sales by the federal government of so-called “surplus un-alloted lands,” the portions of reservations remaining after enrolled tribal members received provisional title to their individual land allotments. A Salish Kootenai man named Michel Pablo had maintained a herd of several hundred bison on the Flathead lands, but the reservation’s privatization threatened his access to sufficient grazing land, and he sold the animals to the Canadian government to form the nucleus herd for Buffalo National Park, established near Wainwright, Alberta, in 1909. By the coming of the Second World War, the animals had perished, and the park was converted into a bombing range.7 Russell’s patrons wished to see him as an authentic visionary of the northern front-country’s roadless wild past, yet the Flathead bison he saw rounded up departed Montana for Alberta by rail.

Meat and Companionship

Russell’s hunting images also emphasize muscle as a symbol of sustenance. While galloping horses provided muscular mobility, herds of bison and cattle provided muscular meat on the hoof. They also suggest the ultimate status of nature as property and animals as livestock, whether companion animals, like horses to be ridden, or bison and cattle to be sold or slaughtered.

Russell was a storyteller who supplemented illustrations with irreverent short stories he recounted in letters to friends, many of which eventually appeared in his posthumous collection of tales, Trails Plowed Under. One notable example recounts a story about a tailless dog named Friendship who lived with an old man by the name of Dog Eatin’ Jack. The dog eater nearly starved to death while frozen in the mountains. During these hungry months, Jack’s famished hallucinations brought him near to murdering and eating his canine companion, an urge from which he managed to retreat. Later, though, a fever dream of oxtail soup convinced Jack of a compromise: He whacked off Friendship’s tail while the dog slept, planning to cook it. The dog ran off, yelping in pain, but both man and dog survived, and they eventually reconciled after the spring thaw.8

Transgressing the sacred boundary between livestock and companion animal, Russell’s matter-of-fact presentation heightens the story’s moralistic ambiguities in ways that open space for reflecting on several forms of animal-human relations, particularly the fraught proximities of petkeeping and meat eating. The late stages of Russell’s career witnessed major transformations in both practices. For one thing, Americans in the early decades of the twentieth century were eating more animals than ever before, thanks to an enormous amount of unprecedentedly cheap beef slaughtered and packaged in industrial facilities. These “disassembly plants” centralized American meat production and removed it from the barns, homes, streets, and myriad other intimate places where workers had killed, bled, and butchered animals in previous centuries, relocating them to industrialized sites outside the public view. Legislative passage of the Meat Inspection Act in 1906 also marked sanitation as a rising priority for the first time in American history. In fact, for the rest of the twentieth century, subsequent regulatory additions effectively criminalized as a menace to public health most informal animal slaughter and meat production outside of certified industrial packing plants. This resulted in a curious paradox, where the more meat that Americans produced and consumed, the fewer animals they tended to encounter. Blood, guts, feces, and rubbish of meat animals were once widely strewn elements of the American landscape, but now they were out of sight. The industrial centralization of slaughter that occurred during Russell’s lifetime had fundamentally estranged most Americans from the animals they ate.

Alongside this transformation occurred a rise in American petkeeping, correlated so closely to the rise in meat consumption that the cumulative sum of money spent on both rose in tandem throughout the first half of the twentieth century. A multitude of historical circumstances made pets—particularly dogs and cats—the solution to modern Americans’ emerging anxieties about animals. For one thing, as period commentators noted, modernity’s social alienations drove men and women to seek solace in companion animals, fulfilling a need for “fidelity” in an era of upheaval.9 Likewise, the replacement of horse-drawn transportation with automobiles in both urban and rural regions transformed the equine-dominated veterinary profession. As clinicians actively diversified their practices to include a larger portfolio of customers, they found pet owners to be among the most lucrative, and the sudden availability and modest expense of small-animal medical expertise established a new infrastructure of pet care that broadened the petkeeping tradition to the American middle classes.10 No longer a symbol of affluence, companion dogs and cats may have remained welcome members of wealthy households, but the elite sought other animals to domesticate.

Patronage and Petkeeping

Russell, by all accounts, disliked pets. He seemed unsettled by the historical transformations that put puppies in children’s laps, and his work remarked on the irony of Americans’ embrace of pets at a time when meat animals were kept out of sight in slaughterhouses and stockyards. He placed pets within the modern household that served as the foil for his nostalgic angst and desire for the open range. His nephew remarked, “When Charlie chose he could tell [a] story in a way that would make a dog lover grind his teeth. For Charlie was sometimes perverse, and anyhow, his animal affections were for horses.”11

Aside from horses, Russell’s family kept no pets, at least while Russell was alive. According to Frank Bird Linderman’s daughter Wilda, in the years before Russell’s death, when her family spent the winter in Santa Barbara, California, leasing a house next door to the Russells, Charlie and Frank walked the beach together routinely with Frank’s dog, a collie named Kim.12 After Russell’s death in 1926, several photographs from family albums show a cocker spaniel, posed most often with an adolescent Jack, the Russells’ son, whom they adopted in 1916 (fig. 5.6). In one of these photos, Jack is disembarking with the dog from a motorboat on Lake McDonald; all the others were taken at Trail’s End, the house in Pasadena that the Russells were building when the artist died (fig. 5.7). A less ubiquitous breed in the twenty-first century, the cocker spaniel epitomized American bourgeois petkeeping a hundred years ago. It was one of the most popular breeds of household dogs from the 1920s through the 1950s. Whether Nancy and Jack acquired the dog in California, Montana, or elsewhere is unclear. But given his loud aspersions about both cars and pets, one can only imagine Charlie rolling in his grave at the thought of them chauffeured across the American West in a Lincoln, cocker spaniel perched across their laps.

Russell’s dislike of household pets extended to small barnyard animals, which he considered undignified aberrations of nature. Linderman’s recollections of Russell include several accounts of an incident at Lake McDonald that concerned some hens Nancy had bought as chicks in Great Falls and raised in an electric incubator. The Russells brought the hens to Bull Head Lodge, and one of them hatched a chick. The hens and the chick apparently aggravated Charlie by imprinting on him and continually following him around the property. Frank observed Charlie throw a stick at the flock in frustration after failing to shoo them away. Frightened, the birds scattered, and one of the hens in the melee appeared to peck at the chick. “‘Get out of here, you unnatural bitch,’ he cried hotly, hurling a stone at the hen.” Linderman continued that Charlie then turned to him and exclaimed: “‘If these smart fellers don’t quit foolin’ with things tryin’ to beat God Almighty at His own game,’ he declared bitterly, ‘we’ll all be tryin’ to eat each other one of these days just like that damned incubator hen.’’’ Charlie’s consternation fell on Nancy, too, for bringing the birds to Bull Head Lodge in the first place; their idyllic summer retreat was “gettin’ more like a farm every day,” he declared, undercutting his desire to escape to a wilderness setting unfettered by human alteration.13

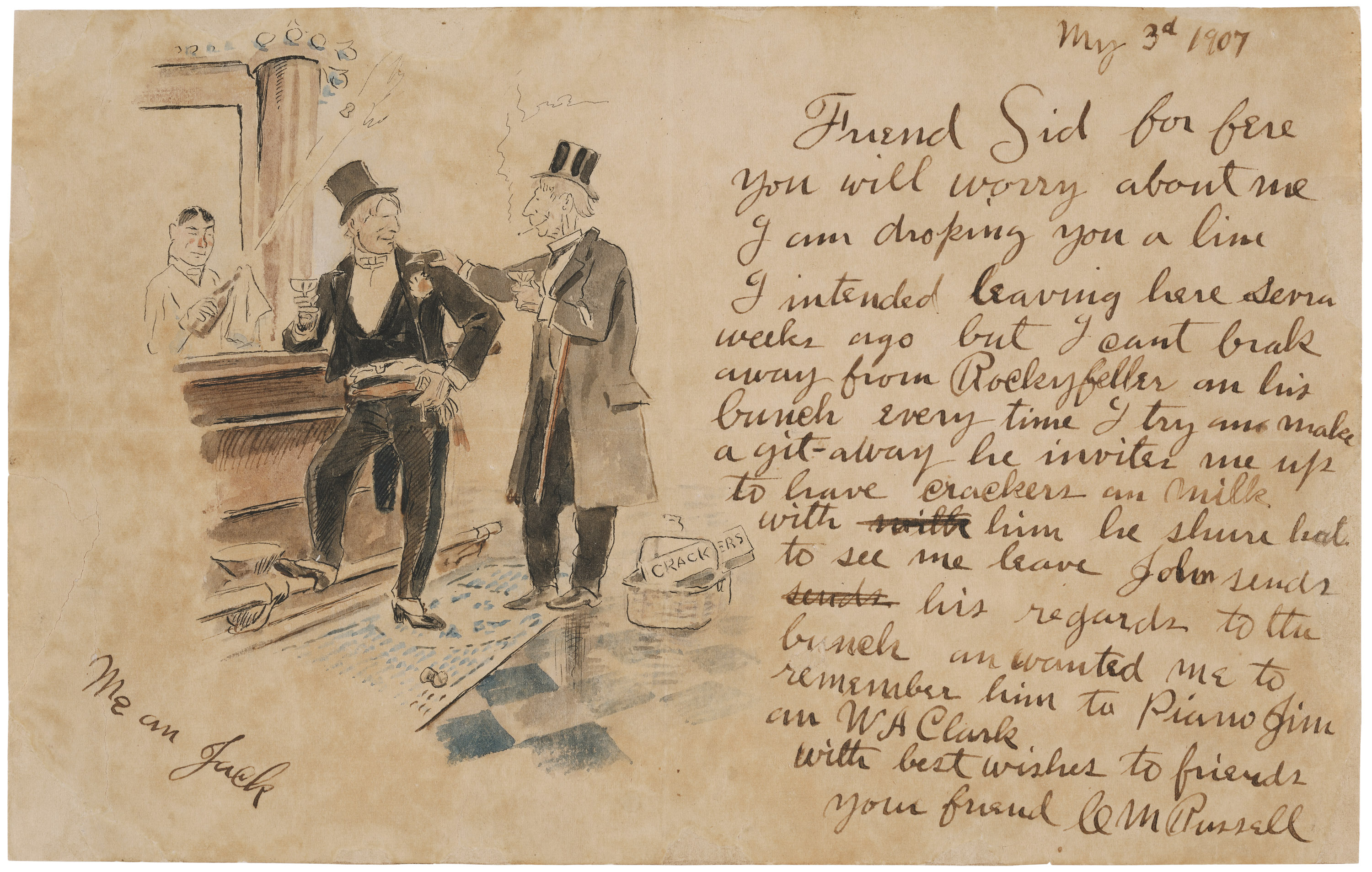

Russell’s desire for a “vacation house in nature” was not unique during his time, an era marked by a post-frontier wilderness fetish that drove deskbound and anxious settler-colonial White men crazy in their pursuit of the so-called strenuous life. However, the vehemence of his reaction to the pecking hen at his summer place, as well as his overall aversion to pets in contrast to wildlife, indicated that Russell was bedeviled by a more extreme kind of fragility, one stemming from his own status as a kept pet. His livelihood depended on the affections of his patrons, a fact he understood uncomfortably. Joking in a letter sent from an exhibition in New York to his friend Sid Willis, the owner of the Mint Tavern in Great Falls, Russell reported, in his rustic prose, that “I intended leaving here sevra [sic] weeks ago but I cant brak away from Rockyfeller an his bunch every time I try and make a git-away he invites me up to have crackers an milk with him he shure hates to see me leave” (fig. 5.8). In short, Russell’s recognition that he and his art had become a plaything for the rich demonstrated his own domestication. Like a household kitten stroked and mollycoddled, Russell relied for his professional life on the wealthy’s affections in ways that communicated class dominance. In a reflection of the cultural theorist Yi-Fu Tuan’s observations about the relationships of petkeeping, Russell, as the pet, lived as a mutual object of dominance and affection in the eyes of his patrons.14

The wealth of Russell’s patrons in many cases also derived from the dominating forces of change against which Russell purported to array his persona. Philip G. Cole provides a good example. Twenty years Russell’s junior, Cole was raised in Montana and headed east—rather than west—as a young man. Son of the Speaker of the Montana Territorial Senate, Cole went to boarding school at Phillips Academy, Andover, and graduated from Princeton in 1906, the same year Charles and Nancy purchased Bull Head Lodge. In the meantime, one of his father’s successful investments in the nascent automotive industry elevated the family further when he acquired the patent for the Schrader tire valve (the same valve used to air up car tires today, as well as many bicycle tires and other inflatables). Cole took over directorship of the company and moved to New York to manage the business, built an estate overlooking the Hudson River, and spent the next three decades filling it with one of the nation’s largest collections of western-themed paintings and sculptures, some of which are now held at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. In short, the scion of the automotive pneumatic tire became one of horse-loving Russell’s most reliable and necessary customers.

One way, of course, that Charlie avoided reconciling his anti-automative performances with the relative financial largesse that industrialist art collectors like Cole afforded his family was that his wife famously handled his business affairs. Nancy set up the exhibitions, arranged travel, negotiated sales, mediated press contacts, and corresponded with clientele. She excelled at these challenging tasks, and her years of hard work were evident in her extensive papers that came to William Britzman when he purchased her home, Trail’s End, with all its contents following her death in 1940.

Nancy’s functioning as the intermediary between Russell and his patrons allowed Charlie to maintain a fictive independence from the forces of automobility, money, and power funding his life and his work. “Should a genius marry?” asked a feature on Russell’s exhibition in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune in 1919. “Should the man who can give the world a masterpiece be chained to the domestic commonplaces of everyday life—shaking down the furnace, shoveling snow from the walk, beating the carpets and doing the hundred and one other things that married life calls for?” Charlie answered with a simple “yes,” going on to describe the complementary life he shared with Nancy as “a fifty-fifty game”:

I wouldn’t drive one of those pesky cars for love or money. My favorite is still the horse. But just the same, I let Mrs. Russell have two automobiles and she lets me keep two horses. It’s a fifty-fifty game with us and I have never felt that domestic relations were in any way a hindrance to a career.

In fact, the Russells’ marriage was vital to Charlie’s career. Only with Nancy’s assistance could Charlie participate fully in the emergence of modern America while maintaining his popular persona as a wilderness-loving outsider. Thanks to Nancy, it could be that when the Minneapolis press repeated the phrase “straight out of the 1880s,” they were remarking on Russell himself, not on his art.15

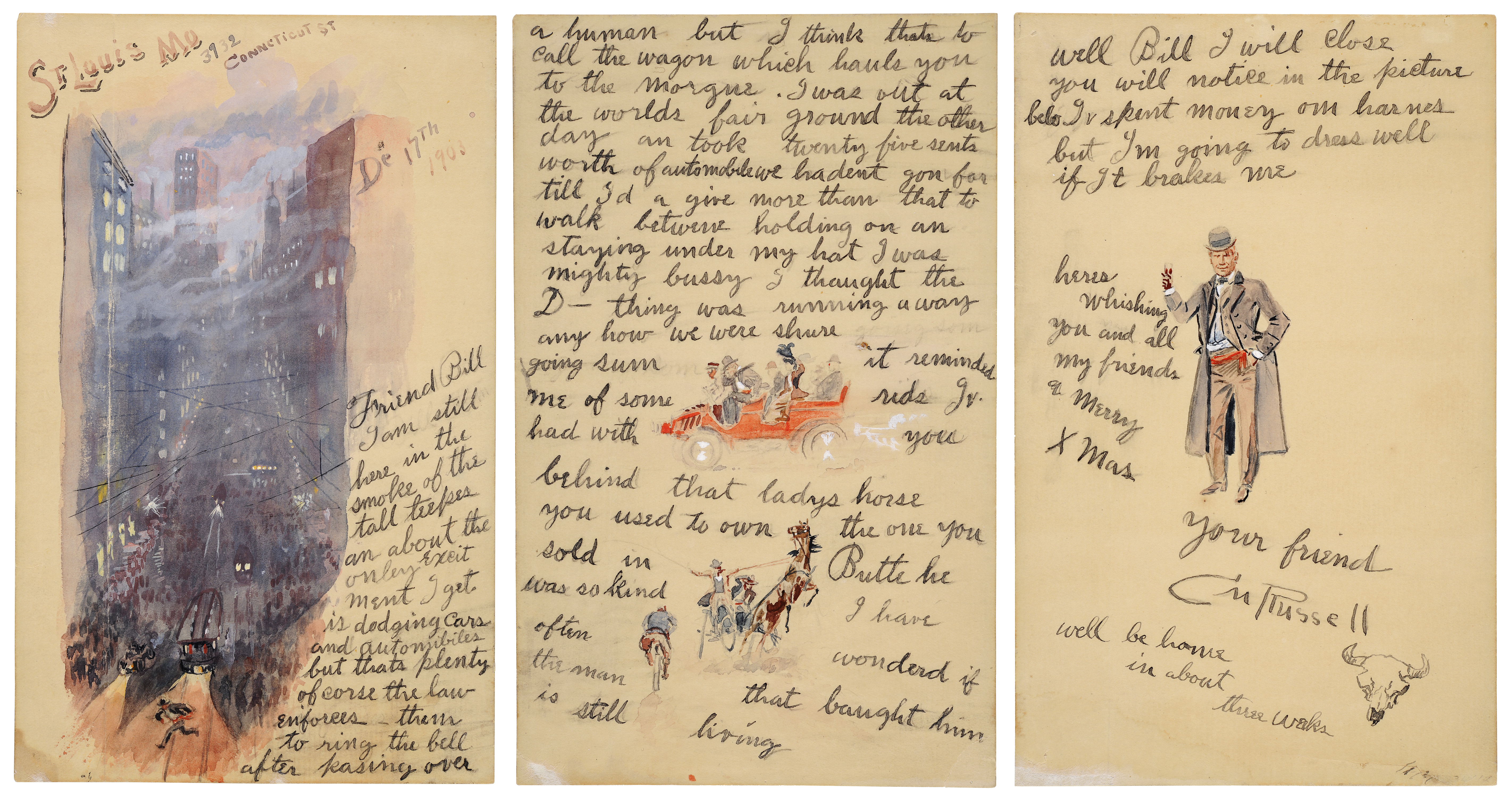

The shift to automotive transportation that occurred during Russell’s lifetime irrevocably altered animal-human relationships in ways that have still not been fully understood. Predictably, Russell groused about this dynamic change in a 1903 letter from St. Louis to his friend William H. Rance back in Great Falls: The “onley excitment [sic] I get [here] is dodging cars and automobiles” (fig. 5.9). Russell’s western art represented not only a nostalgic, masculinist throwback to the “frontier era” but also an expression of angst at revolutions in mobility that threatened conventional notions of dominance, affection, metabolism, and property. As a historical source, Russell’s work suggests the significance of a great divide in American history constituted around these reorganizations of animal and human muscle power, and interpreting Russell’s expressions from this perspective provides new opportunities to consider the significance of his work.

Endnotes

-

“Cowboy Vividly Paints the Passing Life of the Plains,” New York Times, March 19, 1911, Magazine, p. 5. ↩︎

-

A number of works of animal history have attended to these patterns of animal-human relationships near the turn of the twentieth century, including Sarah Amato, Beastly Possessions: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015); Matthew Cartmill, A View to a Death in the Morning: Hunting and Nature through History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Susan D. Jones, Valuing Animals: Veterinarians and Their Patients in Modern America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002); Jennifer Mason, Civilized Creatures: Urban Animals, Sentimental Culture, and American Literature, 1850−1900 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005); Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008); and Michael D. Wise, Producing Predators: Wolves, Work, and Conquest in the Northern Rockies (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016). ↩︎

-

Brian W. Dippie, “‘It Is a Real Business’: The Shaping and Selling of Charles M. Russell’s Art,” in Charles M. Russell: A Catalogue Raisonné, ed. B. Byron Price (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007), 7. ↩︎

-

Robert Marshall, “The Problem of the Wilderness,” Scientific Monthly 30, no. 2 (February 1930): 141−48. For broader discussions about the history of roads and wilderness activism, see David Louter, Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington’s National Parks (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009); and Paul Sutter, Driven Wild: How the Fight against Automobiles Launched the Modern Wilderness Movement (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005). ↩︎

-

Sara Dant Ewert, The Conversion of Senator Frank Church: Evolution of an Environmentalist (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 2000), 35. ↩︎

-

Jon T. Coleman, Nature Shock: Getting Lost in America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 242. ↩︎

-

For greater discussion of the Pablo herd sale and the allotment of the Flathead Reservation, see Wise, Producing Predators, 105−7. ↩︎

-

Charles M. Russell, “Dog Eater,” in Trails Plowed Under (New York: Doubleday, 1927), 129−32. ↩︎

-

Kathleen Kete, The Beast in the Boudoir: Petkeeping in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022). ↩︎

-

Susan D. Jones, “Pricing the Priceless Pet,” in Valuing Animals, 115−40. ↩︎

-

Austin Russell, C. M. R.: Charles M. Russell: Cowboy Artist, a Biography (New York: Twayne, 1957), 125, cited in Raphael James Cristy, Charles M. Russell: The Storyteller’s Art (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2004), 294. ↩︎

-

Wilda Linderman, “As We Remember Mr. Russell,” in Frank Bird Linderman, Recollections of Charley Russell, ed. H. G. Merriam (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 117−28. ↩︎

-

Linderman, Recollections of Charley Russell, 89−90. ↩︎

-

Yi-Fu Tuan, Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984). ↩︎

-

“Minneapolis Views Wild West through Eyes of Montana Cowboy Artist,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, December 14, 1919. See also John Taliaferro, Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003), 117−18. ↩︎